Originally published on July 31, 2024

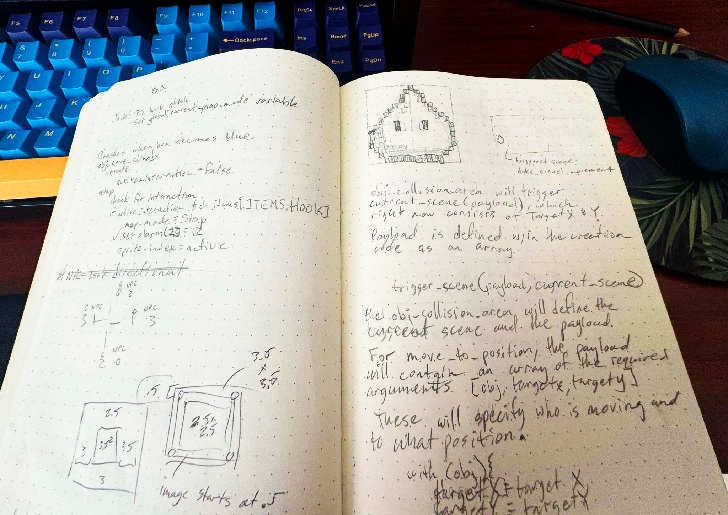

Occasionally, I’ll seek out productivity advice to see if there are any ways I can rearrange my schedule or refocus my time to make more progress on my ongoing projects. One thing that constantly comes up is getting up early, something that doesn’t come naturally to me. Back when I initially started developing Sad Land, I was working from home five days a week, so fitting development time into my schedule before my morning coffee didn’t take much effort. I’d roll out of bed and put in an hour or so of game development and then move on with the rest of my day. The project was new, which meant I was excited to get up and work on it, hitting big milestones every few days. One week I’d get the dialogue system functioning, the next week movement or the interactive pause screen. Before long Sad Land looked, sounded, and played like the game I had imagined making. This progress only lasts so long before you start getting in the weeds. Much like sculpting a statue—breaking away large hunks of stone to reveal the arms, the legs, the head—it feels like a lot of progress and gives the work a distinct form, but it is the detail work, the act of chiseling away at the rough clumps of raw material, that brings life to the hands, the fingernails, the eyebrows, etc. It is all those precious details that take the most time but make the touched stone into a work of art.

Around the time this honeymoon period ended, my day job switched from a remote position to hybrid. Prior to the pandemic, I had been commuting five days a week, so this new hybrid schedule did leave more free time than I might have had in 2019, but the switch back to the office, albeit it not every day, shifted my schedule just enough for me to gradually drop my morning development time altogether. It felt good to sleep in, and I told myself nights and weekends would be a comfortable way to move forward with the project. Weekends have always been the most important swaths of time to code and design for hours on end, but nights became more and more about relaxing after a long day and unspooling a tired brain.

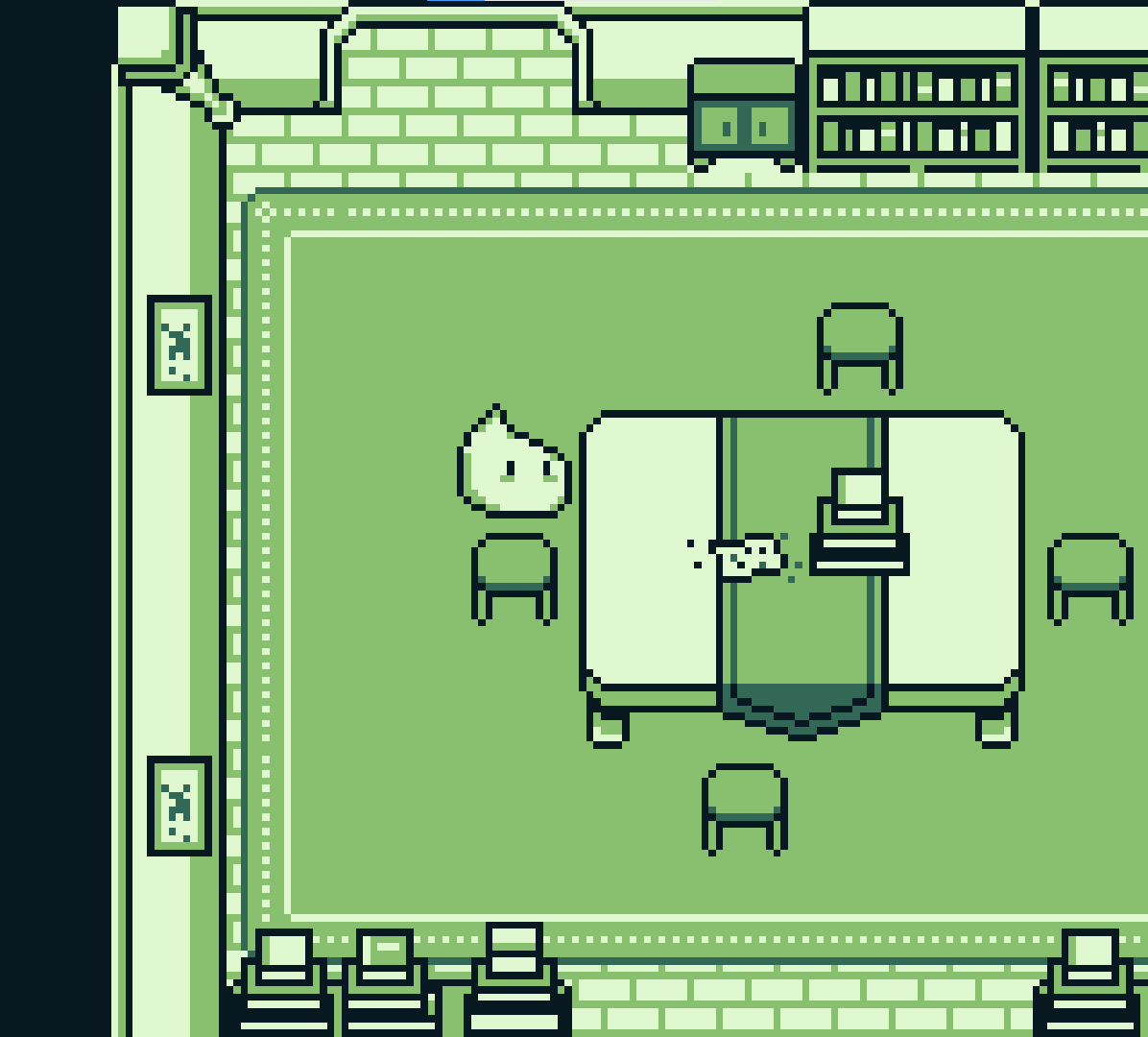

Last week, I was thinking about the project and realized that unless I make some changes to my work habits, I’ll never finish the game as planned. That thought as well as watching DevDuck’s recent video My Day Balancing Indie Game Dev + A Full Time Job led me to the conclusion that waking up early and getting a solid chunk of game development work done before my day job is really the only way to push the project forward even if I love staying up late and sleeping in. This is something that has worked for me before and, for the last week or so, fitting in 2 hours of development on days I work from home and 1 hour on days I have to commute has pushed the needle forward on this project more than I had even imagined. In taking this head-on approach, I have discovered that the new area I’ve been working on (something I wrote about in my May 2024 newsletter) works perfectly as a demo in and of itself. It is short, works well enough as a vertical slice of the project, has plenty of memorable moments, and is a self-contained chapter. This new focus on getting this smaller demo out the door allows me to focus on a much smaller section of the game and polish only the mechanics and story beats in that area of the game. I’m so excited to share this fun little project with the world, and the notion of getting the demo out sooner rather than later is a lovely prospect.

In Rome, cats use motorcycles as their main mode of transportation.

Last month I wrote about my experience visiting historic locations in Rome, but there’s another experience I had traveling that I’d like to explore in this month’s newsletter. While enjoying the afternoon sun and eating mango gelato, walking down the cobblestones streets past the Piazza de Santa Maria in Trastevere, I had the vague impression that I was inhabiting a video game. This feeling wasn’t exactly new to me. I’d felt the same thing in a more intense way when I first went to Disneyland back in 2022. There can be a surrealism to travel, immersing yourself in a different cultural landscape, different architecture, different languages, even different types of pizza. Hell, acclimating to a new time zone can feel like the laws of time and space are shifting under your feet. Jet lag is its own special kind of cosmic horror.

Piazza de Santa Maria as seen on Google Street View.

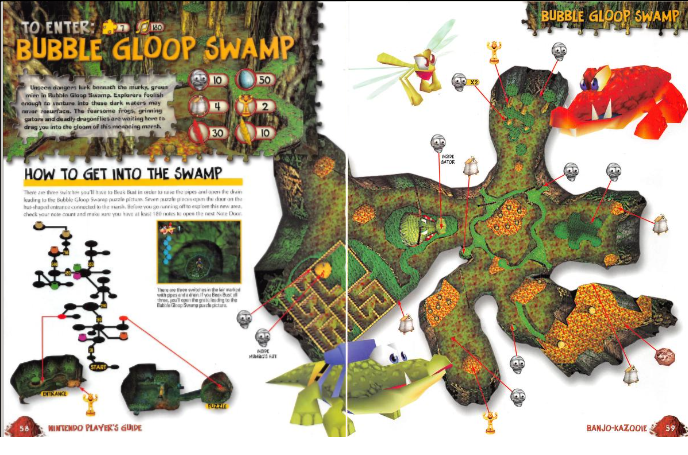

But I knew that what I felt as I was finishing up my melting gelato was not rooted in romanticizing or glamorizing my experience in the plaza but noticing familiar design patterns in the landscape. The fountain in the center of the plaza acted as a central hub with five streets jutting out at the edges of the square, inviting spokes leading to other destinations. The space was intuitive, readable, and natural for the pedestrian. You come across cars, bikes, and Vespas, but those streets are made for walking, and that’s just what you do. Every storefront is designed to catch your eye as you walk past. Drivers often navigate around pedestrians, not the other way around. Over hundreds if not thousands of years, the neighborhood has acted as a social and commercial space meant to be explored slowly on foot, unlike more modern urban designs you see, especially in America, a place I’ve spent the vast majority of my life.

Map of Bubble Gloop Swamp from the official Banjo Kazooie Nintendo Player’s Guide, an example of a video game map with a central location with five paths, each leading to a different point of interest.

This brings to mind a short piece I heard last year on the design podcast 99% Invisible. Producer Delaney Hall discussed the prevalence of stroads (a portmanteau of the words ‘street’ and ‘road’) in the United States, something Hall defines as “a thoroughfare that basically tries to do two incompatible things at once. And in the process, it does both things badly.” Creating a walkable space that accommodates cars in this way creates traffic and makes it more dangerous for pedestrians. For any Bostonians reading this, Newbury Street is closer to a classic street (a destination, convenient for pedestrian foot traffic especially when they shut down traffic in the summer), and Storrow Drive is a road (a way, of course, convenient for uninterrupted travel from point A to B). If you see strip malls, gas stations, and are constantly hitting red lights, you’re on a stroad. In the piece, Hall explores this concept and its history with the help of Charles Marohn, a civil engineer, urban planner, and inventor of the term stroad. She states:

…the value placed on car-based mobility also created this situation we’re in now, where a lot of us live in communities that aren’t quite cities and aren’t quite towns, and where stroads are really the bedrock of that suburban development style. And so over time, we’ve just built a lot of places that are very car dependent, and they just prioritize cars over people.

I mention this because, as an American, existing in any densely populated walkable space with far more people than cars is novel. Most of my experience navigating spaces like this is strictly digital. During my first playthrough of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, I opted out of fast travel, a common feature in video games that allows the player to instantly teleport to areas around the game map. While traveling on foot in BotW is presumably faster and more efficient than physical meat space, the map is still estimated to be around 30 square miles, which is roughly the size of Providence, RI, and Pawtucket, RI, combined. While this was a terribly inconvenient way to move from place to place, it added a unique dimension to the gameplay experience.

Author and game designer Ian Bogost has a chapter in his book How to Do Things With Video Games on transit where he explores concepts from German cultural studies scholar Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s work The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the Nineteenth Century, a book about how new modes of transportation alters the perceived experience of space and time. Bogost writes:

The carriage or horseback had provided a relatively unmediated view of the passing landscape. If the traveler so wished, he or she could interrupt a journey and step down from the coach to inspect a vista or to meander into a meadow. But even from his or her seat, the traveler experienced a more deliberate revealing of scenes along the route. That changed with the railroad, which bombarded ever forward, along the single path afforded by the iron road, each particular scene visible through the railcar’s window for only a brief moment. If the carriage functioned more like a landscape painting, the railway functioned like a cinema camera…

…And of course today, in the era of the airplane, the vistas of travel have been removed entirely, replaced by the white blankets of clouds or the vague pattern of farmland five miles below.

…And of course today, in the era of the airplane, the vistas of travel have been removed entirely, replaced by the white blankets of clouds or the vague pattern of farmland five miles below.

Rejecting fast travel mechanics early on in the game allowed for a more immersive experience and for me to feel the distance between locations. Visiting the southern seaside village of Lurelin could mean a ten-minute excursion on horseback through a rainstorm. Instead of “vistas of travel,” I would have instead seen a loading screen before arriving magically at my destination. The world is littered with so many side quests and curiosities that I was bound to get distracted on the way, picking up an item or encountering a creature that I would have completely missed during fast travel. Beyond these quantifiable benefits, this commitment to slower travel allowed for a full appreciation of Hyrule’s quiet atmosphere, accentuated by the subtle and ambient piano score. For my second playthrough of Breath of the Wild and my current playthrough of Tears of the Kingdom, I fully embraced fast travel but appreciate my time mindfully exploring Hyrule as I did back in 2017.

Picture I took at sunset on the way back from Petco on the first day of my recent weeklong vacation. Instead of ordering our cat litter online, I drove into the store. This “wasted time” resulted in a relaxing summer drive and this photograph.

I suppose in this newsletter I am advocating for mindfulness in life and efficiency in work. The problem I have with a lot of productivity advice, especially those peddled by productivity YouTube channels and podcasts, is that the life they outline, a life of getting up at 4 AM, of diligent workout routines, of time auditing, feels to me like a hyper predictable life that aims to iron out the things that can make life exciting, meandering, and interesting. Refusing to fast travel in Breath of the Wild added at least 20 hours to my campaign, but taking it slow gave me a sense of adventure that’s rare in any walk of life. My wife and I also spent a lot of time walking to get from place to place in Rome as side streets and street art can be just as part of the travel experience as destination monuments. That said, wandering through a creative life unstructured can keep you from your own destinations, and some productivity advice can be incredibly valuable if you find it works for you.

Next month I’ll be exploring Disneyland’s relationship with games and game design. I was originally going to pair it with this topic of urban design but both ideas proved strong enough to cover on their own. Hope you have a relaxing August and get to swim in a body of water at least one more time before summer’s end!

Sincerely,

Neil

Next month I’ll be exploring Disneyland’s relationship with games and game design. I was originally going to pair it with this topic of urban design but both ideas proved strong enough to cover on their own. Hope you have a relaxing August and get to swim in a body of water at least one more time before summer’s end!

Sincerely,

Neil