Originally published on November 30, 2024

Although development was a little sporadic this month, I was able to find some time to improve and iterate on assets I've shared in the past. I've also been piecing together a system that tracks the player's progress through the demo, triggering new interactions based on certain milestones. This feature isn't complete yet, but I will be sharing more on this in the near future. I'm more confident than ever in the direction the project is going and have been seeing noticeable improvements every week that goes by, which is all you can really ask for with a project like Sad Land.

I launched this newsletter last November and to celebrate that milestone, I thought it would be fitting to reflect on what motivated me to start game development in the first place. Going way back, one of my earliest memories is of receiving an NES on Christmas morning, initially hesitant to play it, as dying in the bottomless pits in the first level of Super Mario Bros. scared me on a deeply existential level. Once I realized that death in video games is not the end of the road but the first step to pushing you to improve, I cozied up to video games and never stopped playing.

I launched this newsletter last November and to celebrate that milestone, I thought it would be fitting to reflect on what motivated me to start game development in the first place. Going way back, one of my earliest memories is of receiving an NES on Christmas morning, initially hesitant to play it, as dying in the bottomless pits in the first level of Super Mario Bros. scared me on a deeply existential level. Once I realized that death in video games is not the end of the road but the first step to pushing you to improve, I cozied up to video games and never stopped playing.

For some time, I viewed video games the same way I viewed everything else in my life and as all little kids do, as just another facet of existence. Every aspect of the world is happening around you and you simply react to it without a firm grasp of how anything actually operates.

At some point, presumably around the time I reached the concrete operational stage of childhood development, I learned that the art we enjoy isn't summoned into existence through magic but made by humans. It wasn't until I watched the 1982 British animated short film The Snowman that I fully understood what that meant.

The 26-minute animated film has a rough, hand-drawn aesthetic, using tools like colored pencils and pastels to preserve the look of the storybook the film is based on. Cartoons I loved, like Looney Tunes and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, were produced using painted animation cels, which to a 7-year-old is impossibly smooth. Seeing the rough, kinetic animation of The Snowman, a look achieved with tools I had hands-on experience with, allowed me to better understand how humans might actually produce animation and, in turn, how impossibly long and difficult the process must be. Since the moment I imagined people creating art, I knew it was something I wanted to do.

Background artist Loraine Marshall from the short documentary Snow Business: the story of The Snowman

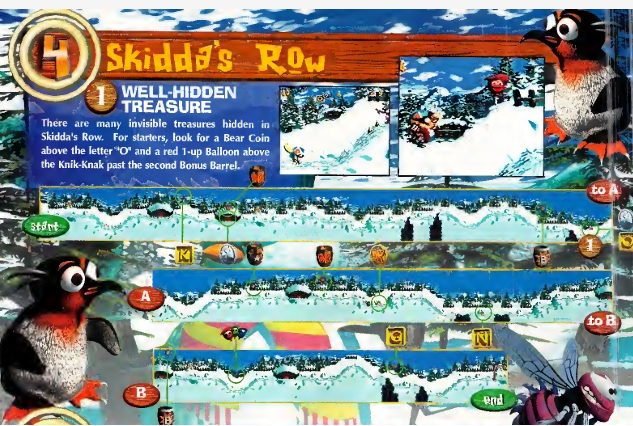

Like many other Nintendo kids of the 90s, I subscribed to Nintendo Power magazine, a monthly publication with information, news, and reviews of games released on Nintendo consoles. Along with tips and promo art, large swaths of the issues were filled with maps of the levels, offering a glimpse into the level designs of games I'd never play. I can't remember ever using these maps to guide me through a level, but the hours I spent pouring over them sparked a desire to draw my own.

An excerpt from Nintendo Power Issue 90 (November 1996) presenting a level from Donkey Kong Country 3: Dixie Kong's Double Trouble!

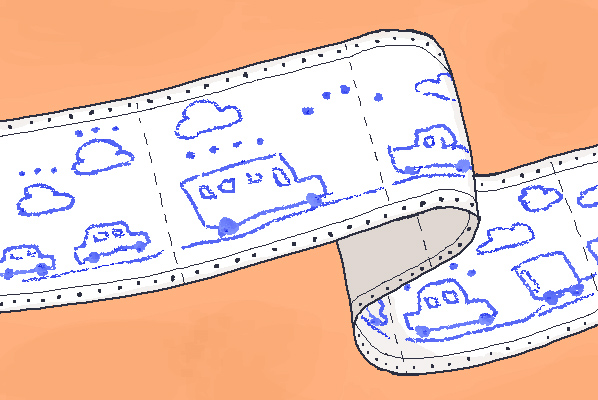

When I wanted to draw something, I'd go into the basement and rip some sheets from a stack of dot-matrix printer paper. For anyone who hasn't had experience with this type of printer paper, the entire ream of paper is connected end to end, the way scratch tickets are stored before a clerk rips one off to sell. Along the sides, each page had thin, perforated strips of holes used to help feed the paper through the printer.

I remember one day pulling out a short stack of dot-matrix paper and mapping out my own level, a platforming stage set on a highway where the player would jump from vehicle to vehicle. My working title for this game was Nacho and Woofy Go to Canobie Lake Park. Inspired by the Disneyland game Adventures in the Magic Kingdom for the NES, this would be my own spin on the theme-park video game starring Nacho the Cat and Woofy the Dog, two original characters my older brother and I created when playing make believe, and the only amusement park I'd ever visited, New Hampshire's Canobie Lake Park. In my mind, the highway level was an obvious first level as – in my personal experience – in order to get to an amusement park, you had to drive on the highway to get there first. I lost interest after designing that first level, having no clear direction and second-guessing my plan to get the game produced – sending it to Nintendo and hoping it was good enough that they'd build it for me. The image above is an illustration I made to convey what that first level may have looked like.

I kept playing video games throughout high school and college but shifted my creative hopes and dreams to writing novels, directing films, or starting a band. As a poor college student, I stuck to playing games from the previous console generation or playing older games on my computer through software emulation.

I kept playing video games throughout high school and college but shifted my creative hopes and dreams to writing novels, directing films, or starting a band. As a poor college student, I stuck to playing games from the previous console generation or playing older games on my computer through software emulation.

A few years after graduation, the spark to develop my own game was reignited with the release of Indie Game: The Movie, a feature-length documentary chronicling the ups and downs of creating and releasing video games independently. Unbeknownst to me, there was a new movement in the video game marketplace for independently produced games. Before digital distribution, to release a commercial video game, you needed to manufacture physical carts or discs and, with the help of a publisher, get those games on store shelves. In 2003, the video game developer Valve, known for the hugely popular games Half-Life and Counter-Strike, unveiled Steam, a new digital storefront. Steam started as a curated platform, but as the years went by it became easier and easier for independent game developers to sell their games on the platform and reach a wide audience.

The documentary chronicles the stories of three games at various stages of development. We see Fez, a cute and colorful puzzle platformer, a game in development that has gone through several iterations and years of publicity without a finished product; Super Meat Boy, a violent and difficult action platformer with a crude sense of humor and an addicting game loop, a completed game on the cusp of release; and Braid, a puzzle platformer with a mind-bending rewind mechanic, an already released title that garnered huge notoriety and sales. All three games harkened back to games of the NES-era, imbued with nostalgia and personalities matching the developers themselves. While in retrospect, it's clear to see how narrow of a slice we get of the overall game development community (a handful of dudes making platformers), it presented, at least for me, a new way of thinking about games. Like watching a couple of kids growing up listening to The Beatles, buying four-track recorders and making their own unique experimental albums, love letters to their favorite band.

I can't say if the documentary would dazzle me in the same way if I watched it for the first time today or what an Indie Game: The Movie would look like in 2024, but the impact of the film at the time, a polished and serious video game documentary premiering at the Sundance Film Festival, defined a scene and a roadmap to success, whether realistic or not. Regardless, the film still means a lot to me as an account of a bunch of weirdos funneling a lot of passion into a project they truly believe in. It acted as a portal into the world of independent video games, treating it as a more serious academic pursuit instead of a pastime. It acted as an invitation to the world of stories and design philosophies surrounding video games instead of seeing them just as a pastime.

It's that line of thinking that, years later, lead me to pick of Derek Yu's Spelunky, a memoir about Yu's process and journey making his hit indie game Spelunky.

Spelunky is a 2008 procedurally-generated action platformer inspired by pulp adventure fiction like Indiana Jones. With its high difficulty and level maps changing every time you initiate a new run, each time you start over captures the experience of dropping yet another quarter into an arcade cabinet.

At the time, I hadn't played the game itself but had heard the book recommended countless times online. Reading the following passage from Derek Yu's memoir was the push I needed to take all my interests, all my knowledge, all my experience, and start work on my own games:

At the time, I hadn't played the game itself but had heard the book recommended countless times online. Reading the following passage from Derek Yu's memoir was the push I needed to take all my interests, all my knowledge, all my experience, and start work on my own games:

Until recently, programming was the crucial gatekeeper to making games. Early in the history of video games, the lead programmer was typically also the lead writer, artist, and designer. If you could program software, you could be a game creator. You may not have necessarily been able to craft a good game, but at least you could try. If you weren't a programmer, you needed to find one. The advent of game-making tools like Klik & Play and Game Maker changed the landscape of game development drastically, putting less of a premium on programming and allowing all kinds of new people to make games.

I've tried programming a game engine from scratch before, surrounding myself with books like Tricks of the Game-Programming Gurus in an effort to “make games the right way,” but when days of work yield as much as I could make in Game Maker in a few minutes, it's hard to stay motivated. At the beginning of each semester at Berkeley I had the same sort of naïve gumption, buying pristine notebooks and attentively jotting down everything the professors said, only to succumb to ennui a week later, my notes devolving into irrelevant doodles. Post-school, however, I accepted that I wasn't cut out for academia and programming theory. I no more wanted to program my own game engine than I wanted to fashion my own paintbrushes. This important realization meant I could stop wasting my time trying to be something I wasn't. Instead of being embarrassed about not being a “real programmer” using “real programming languages,” I vowed to make games whichever way felt good to me.

I've tried programming a game engine from scratch before, surrounding myself with books like Tricks of the Game-Programming Gurus in an effort to “make games the right way,” but when days of work yield as much as I could make in Game Maker in a few minutes, it's hard to stay motivated. At the beginning of each semester at Berkeley I had the same sort of naïve gumption, buying pristine notebooks and attentively jotting down everything the professors said, only to succumb to ennui a week later, my notes devolving into irrelevant doodles. Post-school, however, I accepted that I wasn't cut out for academia and programming theory. I no more wanted to program my own game engine than I wanted to fashion my own paintbrushes. This important realization meant I could stop wasting my time trying to be something I wasn't. Instead of being embarrassed about not being a “real programmer” using “real programming languages,” I vowed to make games whichever way felt good to me.

In the summer of 2019, I felt I was at a crossroads in my career and committed myself to learning programming to build up skills that might allow me to enter a more lucrative field and work from home (something that seemed like a pipe dream before COVID). I purchased some cheap online courses and began learning Python and JavaScript in my off hours, dropping pretty much every hobby in pursuit of becoming a competent coder. I logged all my hours on a spreadsheet, and between June of 2019 and March of 2020 I had logged nearly 350 hours between tutorials and coding projects. When I attended PAX East in late-February 2020, where I purchased Yu's memoir, I was primed to start my own journey of video game development.

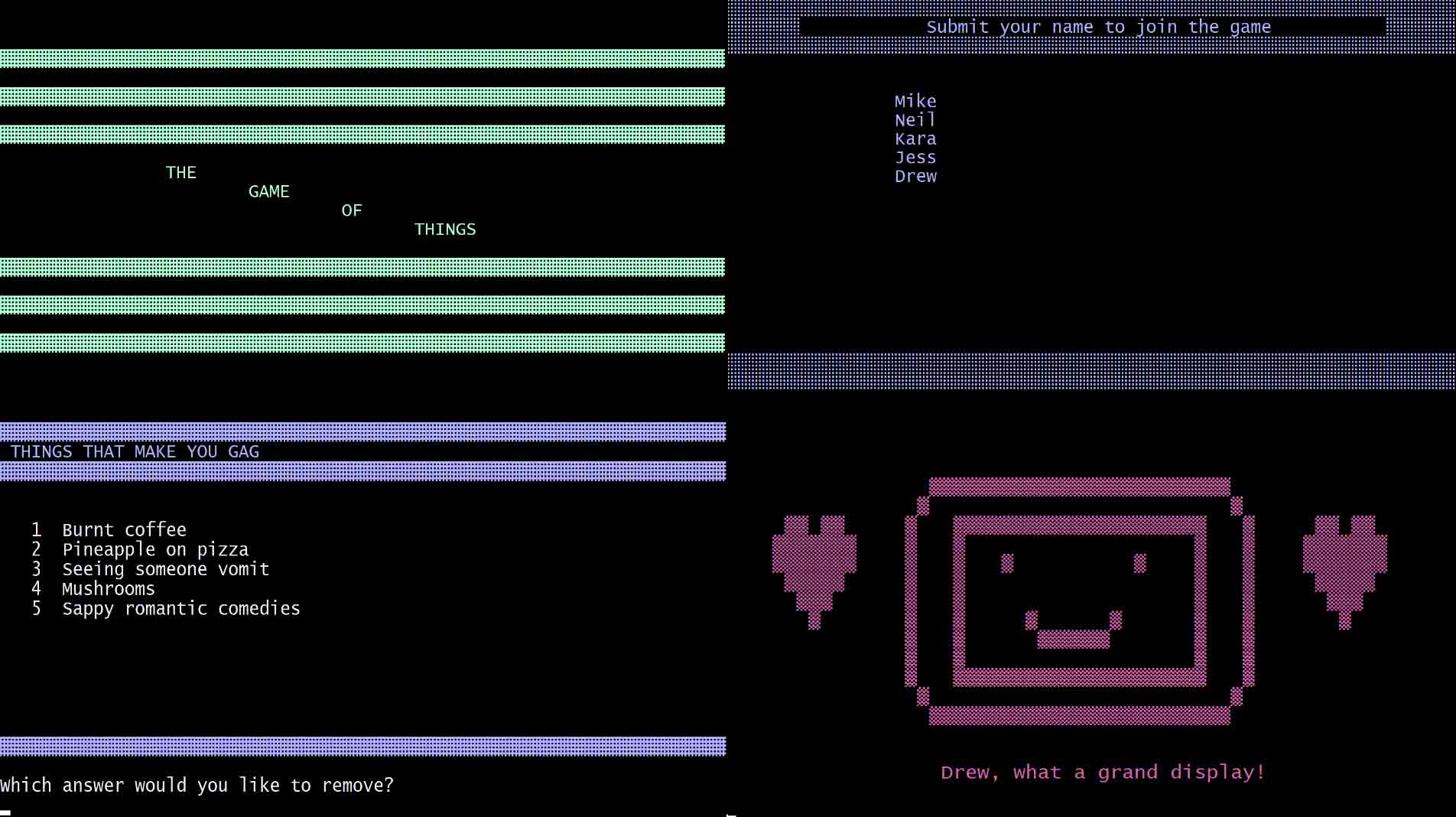

Taking Yu's call to action, I planned my first project, a digital version of The Game of Things to play with my friends over ZOOM. If you haven't played it, The Game of Things is a party game where each round one person reads a prompt, the other players answer that prompt secretly on a piece of paper, and one by one players guess who wrote which response. The rules and format of the game were already laid out for me so I got to work figuring out how I could create the game in Python to be played on ZOOM. I rigged it up so that players could enter their names and responses by texting a digital phone number I'd set up.

Taking Yu's call to action, I planned my first project, a digital version of The Game of Things to play with my friends over ZOOM. If you haven't played it, The Game of Things is a party game where each round one person reads a prompt, the other players answer that prompt secretly on a piece of paper, and one by one players guess who wrote which response. The rules and format of the game were already laid out for me so I got to work figuring out how I could create the game in Python to be played on ZOOM. I rigged it up so that players could enter their names and responses by texting a digital phone number I'd set up.

I played the game four or five times with friends during 2020, and it was very rewarding to share my work with other people. In November of 2020, I went back and reread Yu's memoir, maybe to get some further insight now that I waded into the waters of game development myself. This time, it inspired me to download Game Maker to try and make something more ambitious.

I write this not as a way to self-mythologize but as a testament to all the other creators that bring things to life, shining bright beacons to those paying attention. From works of art themselves (The Snowman, Fez/Super Meat Boy/Braid, Spelunky) to the works exploring how they came to be (Snow Business: the story of The Snowman, Indie Game: The Movie, Derek Yu's memoir), creativity and the act of creation can be truly infectious. That's something I've always been thankful for.

Sincerely,

Neil

I write this not as a way to self-mythologize but as a testament to all the other creators that bring things to life, shining bright beacons to those paying attention. From works of art themselves (The Snowman, Fez/Super Meat Boy/Braid, Spelunky) to the works exploring how they came to be (Snow Business: the story of The Snowman, Indie Game: The Movie, Derek Yu's memoir), creativity and the act of creation can be truly infectious. That's something I've always been thankful for.

Sincerely,

Neil