Originally published on October 31, 2024

I made some decent development progress this month on Sad Land. With most of the back-end functionality complete, for the demo at least, the vast majority of my development time has shifted to dialogue, pixel art, and scene scripting. For those less familiar with game development, scene scripting is the process of writing the code or script for an individual scene or interaction triggered in the game. Basic interactions like talking to an NPC or picking up an item are basic interactions that can be reused, while other interactions like mapping out a cutscene or having NPCs interact with the environment when you start talking to them requires a unique code block. It’s those bespoke interactions that keep the gameplay fresh and interesting.

New assets of the throne and casket from the castle’s Throne Room.

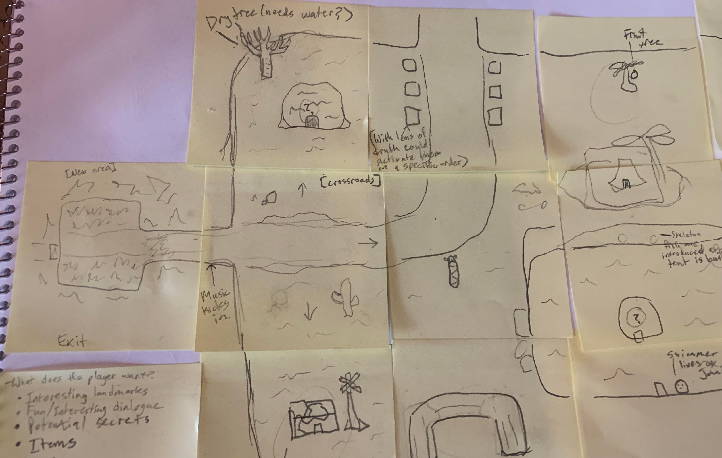

While building out one of the new areas in the demo, I had a revelation that slightly changes my design philosophy for exploration in the game. Last January, I shared a work-in-progress map of the desert area made of post-it notes, wherein I included a point of interest on each post-it in the grid…

The philosophy here is that no matter which direction you’re moving, you will stumble into something worth investigating. As I built out the area, adding new locations and spreading things out to accommodate this new grid, the map felt like it was coming together in a satisfying and natural way.

Upon playtesting these areas with people who’d never picked up the game before, I discovered they would enter the area without much direction and feel lost almost immediately. I thought I’d checked all the boxes – creating a clear path leading to the area’s main point of interest, planting unique monuments, creating distinct zones – but came to the realization that the layout was somewhat at odds with the game’s slower pace of movement. Most backtracking felt tedious, there wasn’t enough player motivation to guide them through the area, and the space wasn’t unique enough for a new player to easily build a mental map.

Upon playtesting these areas with people who’d never picked up the game before, I discovered they would enter the area without much direction and feel lost almost immediately. I thought I’d checked all the boxes – creating a clear path leading to the area’s main point of interest, planting unique monuments, creating distinct zones – but came to the realization that the layout was somewhat at odds with the game’s slower pace of movement. Most backtracking felt tedious, there wasn’t enough player motivation to guide them through the area, and the space wasn’t unique enough for a new player to easily build a mental map.

The new feature I wrote about last month, allowing for more natural camera movement in smaller rooms, is paving the way for a simpler approach for map design. Instead of focusing on larger areas meant for exploration, I can instead lead the player through smaller linear rooms with a few points of interest that will guide them through the space. My overarching goal here is to make sure that something sparks the player’s curiosity every few seconds of movement, hopefully supplying a consistent loop of “movement, curiosity, interaction.” The last thing I want players to be asking themselves is “where do I go?” or “what am I supposed to be doing?”

Last year Mark Brown, video essayist and game developer, released a video on his Game Maker’s Toolkit YouTube channel titled How Nintendo Solved Zelda's Open World Problem, exploring how the designers at Nintendo were able to craft a huge open-world map with fresh surprises around every corner.

Wherever you go and whatever you do, you’ll be given a few new things to catch your eye and attract you. Perhaps that new landmark will distract you and you’ll ditch your old plan and go somewhere new instead. When you’re finished, you’ll remember where you were supposed to go and head back there, only to be distracted again. Whatever the case, this creates a chain reaction, an infinite loop of discoveries, a breadcrumb trail of landmarks. All of which makes you slowly move across the map in an addictive quest of ‘ooh, what’s that?’, ‘ooh, what’s that?’, ‘ooh, what’s that?’

Although the scope and gameplay in Breath of the Wild couldn’t be further from what I’m building for Sad Land, this sense of curiosity and discovery is something I’d like to carry over but in a much smaller and more curated fashion. Consistent player engagement is the top priority here; abject boredom is poison.

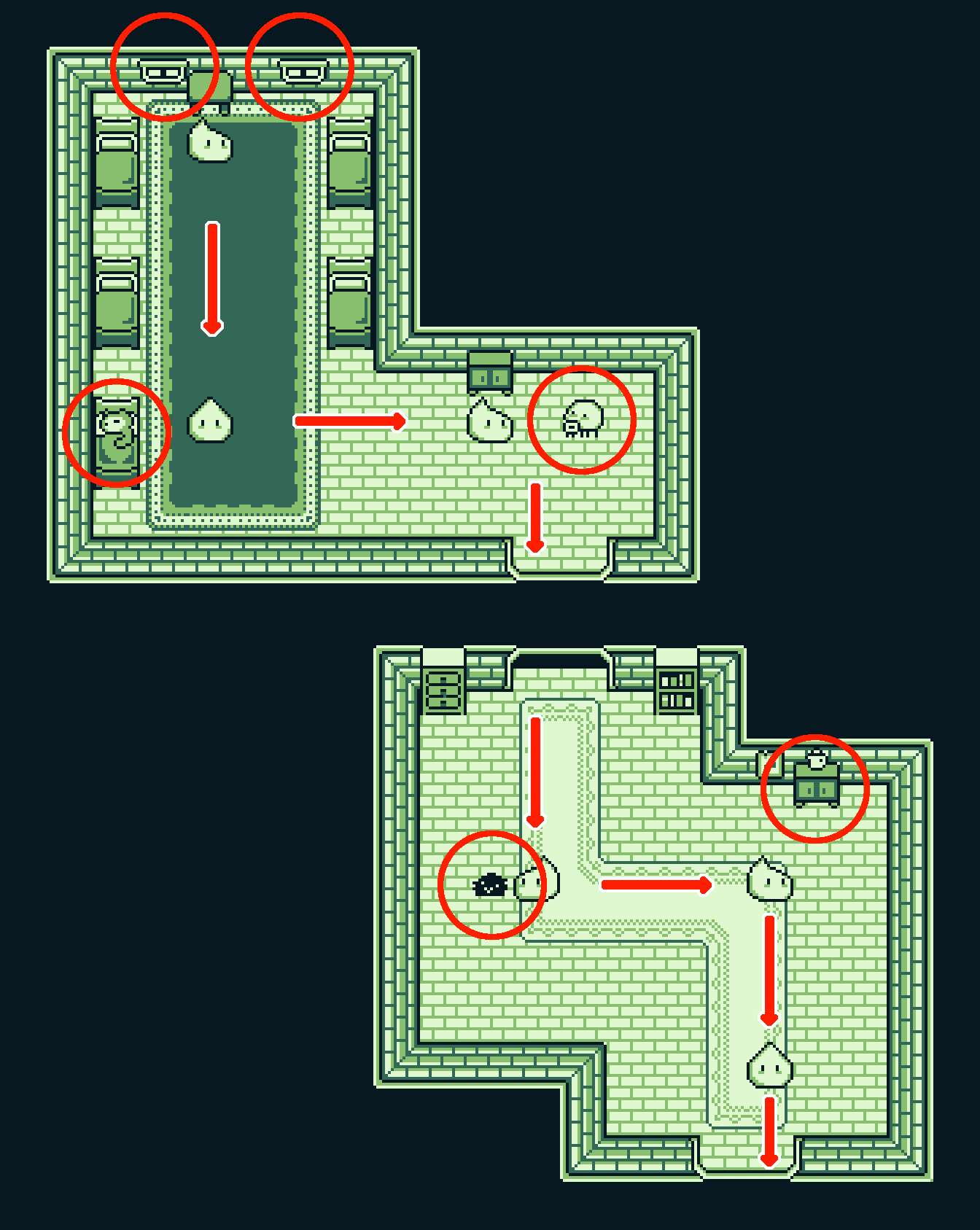

Below is a layout of two different connected rooms in the castle with this design philosophy in practice. Any NPC or object with red circles around them are considered points of interest and the red arrows convey the player’s movement through the space.

Below is a layout of two different connected rooms in the castle with this design philosophy in practice. Any NPC or object with red circles around them are considered points of interest and the red arrows convey the player’s movement through the space.

The player’s intended movement alternates between the x axis (horizontal) and the y axis (vertical), something I naturally landed on as I was laying out the space. The small rooms with this alternating movement pattern reminded me of a blocking technique commonly used by Steven Spielberg. This idea is explored in the video Use the Steven Spielberg "L System" to create screen MAGIC by Sareesh Sudhakaran, a director and cinematographer from Mumbai, where he explains in simple terms how Spielberg moves the camera, his actors, or both simultaneously to compose easy to read and dynamic scenes:

The camera can move in infinite ways, but the two fundamental ways it can move are towards the action or sideways, parallel to it. Spielberg’s camera consistently alternates between the two. You have one shot where the camera moves towards or away, as perpendicular to the frame, and the very next shot it moves sideways or parallel to the frame. Then the process repeats itself. This ensures two frames aren’t visually boring. Our eyes are always working to find new perspectives.

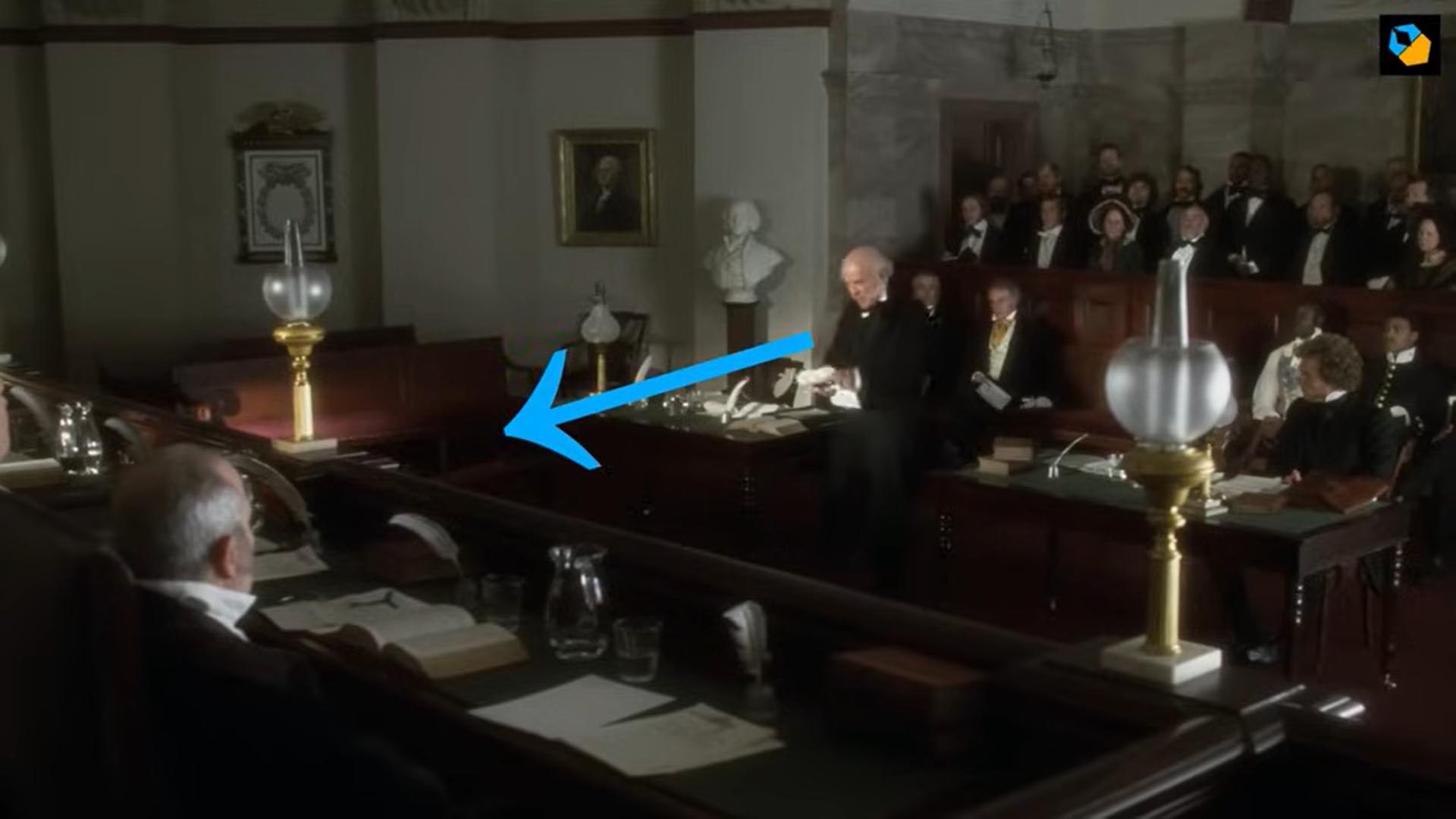

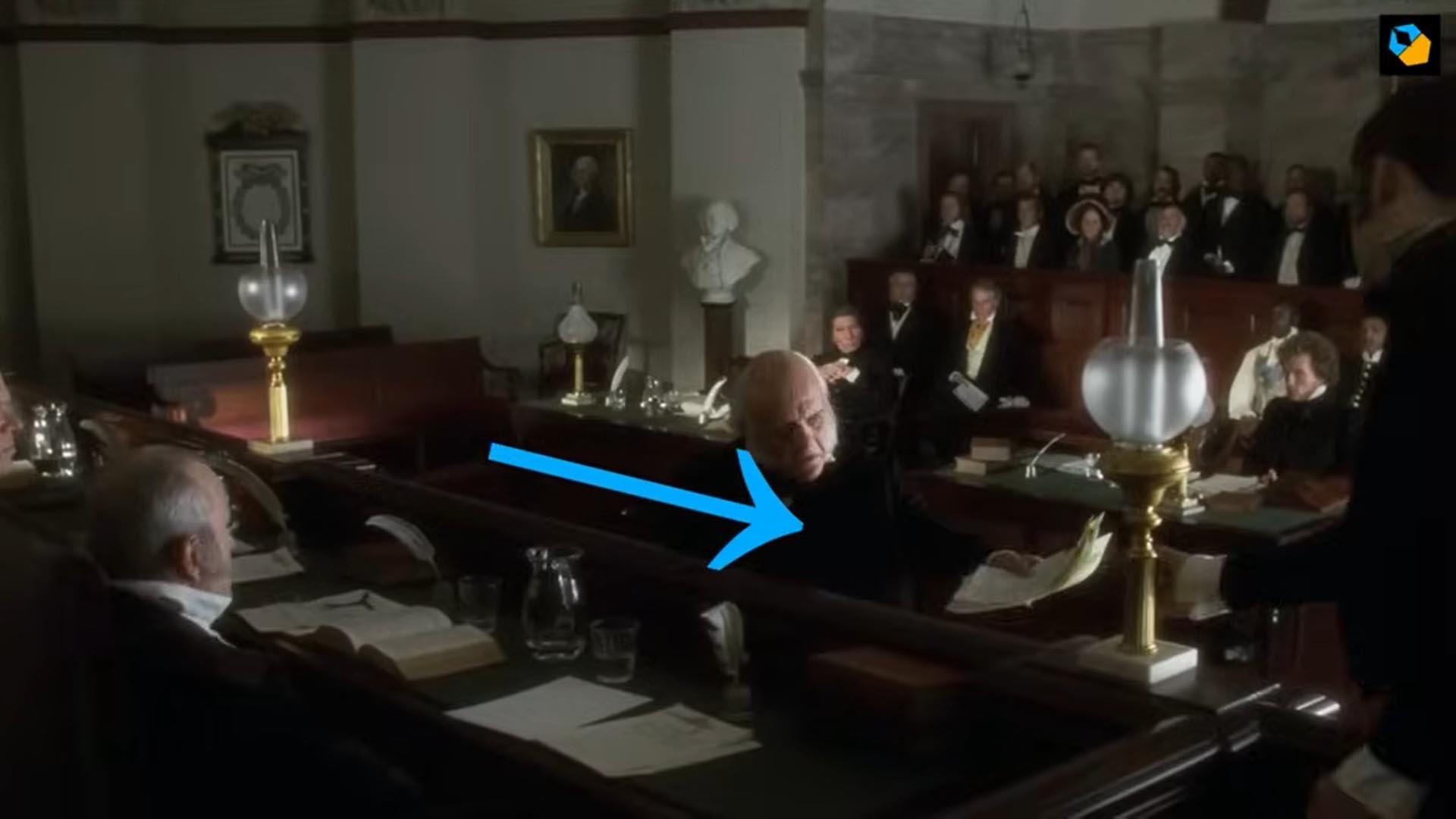

Sudhakaran gives several examples of this concept in practice, including the one depicted below, John Quincy Adams (played by Anthony Hopkins) moving through the courtroom in Spielberg’s 1997 film Amistad.

Here the camera is in a fixed position with Adams as the only object moving in the frame, all eyes in the courtroom are on this character and so are ours. Instead of approaching at a diagonal to hand the transcripts in to be part of the deliberations, Adams moves first forward in a straight line to the front of the courtroom…

Here the camera is in a fixed position with Adams as the only object moving in the frame, all eyes in the courtroom are on this character and so are ours. Instead of approaching at a diagonal to hand the transcripts in to be part of the deliberations, Adams moves first forward in a straight line to the front of the courtroom…

…and then horizontally along the bench. This shot ending with him handing off the documents, completing his action.

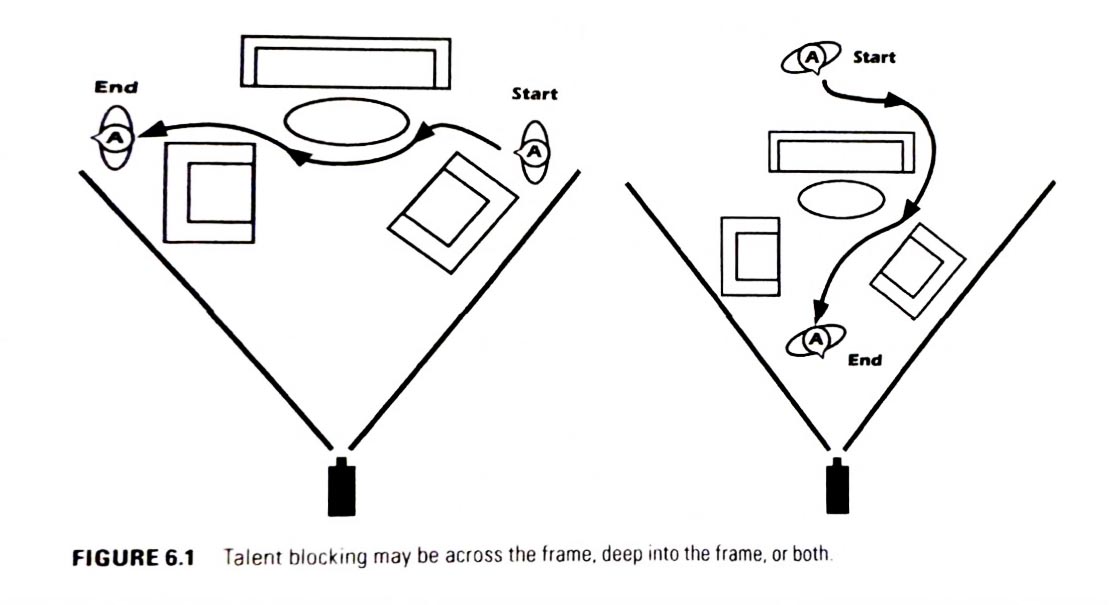

Christopher J. Bowen, long-time industry professional and Associate Professor of Film Production and Visual Media Writing at Framingham State University, writes in his book Grammar of the Shot:

Creating interesting blocking can engage the audience’s eyes and keep them involved with the imagery and in the story. We like to watch things move around the screen. So, talent blocking across the screen (left to right or vice versa) helps to vary the compensation balance in real-time as the shot plays out. Talent blocking deep into the set or location adds to the illusion of a 3D film space and draws the audience’s attention into the compositional depth of the frame.

Diagram from Grammar of the Shot (5th Edition)

One thing Spielberg does well is keep the shots simple and motivated to maximize the movement of the blocking we see on screen, whether that be blocking of the actors or camera. Having the subject of a shot move across the screen (left/right) or moving directly toward or away from the screen is often clear movement that is easy to follow, and when you’re sculpting an action scene it is important for the audience to be able to follow the characters’ movement easily, especially if there are a lot of quick cuts during the scene. This style of blocking allows the audience to focus on the emotion of the scene while keeping momentum and without forcing the viewer to piece together moment-to-moment what is happening on screen.

As an example of an action sequence that does not implement this style of shot composition and editing, I recommend checking out this scene from Michael Bay’s Transformers (2007).

As an example of an action sequence that does not implement this style of shot composition and editing, I recommend checking out this scene from Michael Bay’s Transformers (2007).

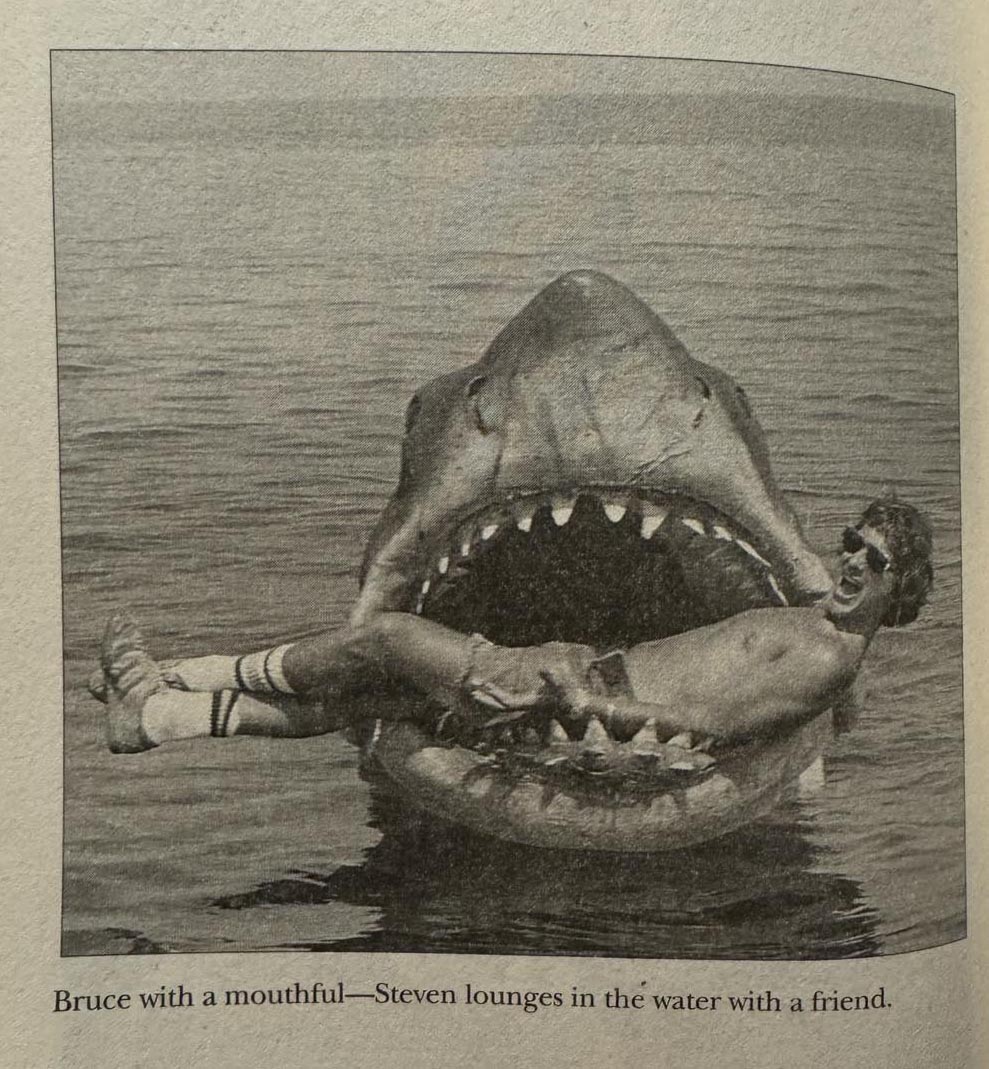

A photo from The Jaws Log by Carl Gottlieb depicts Steven Spielberg screaming for his life moments before he was devoured by a malfunctioning animatronic shark.

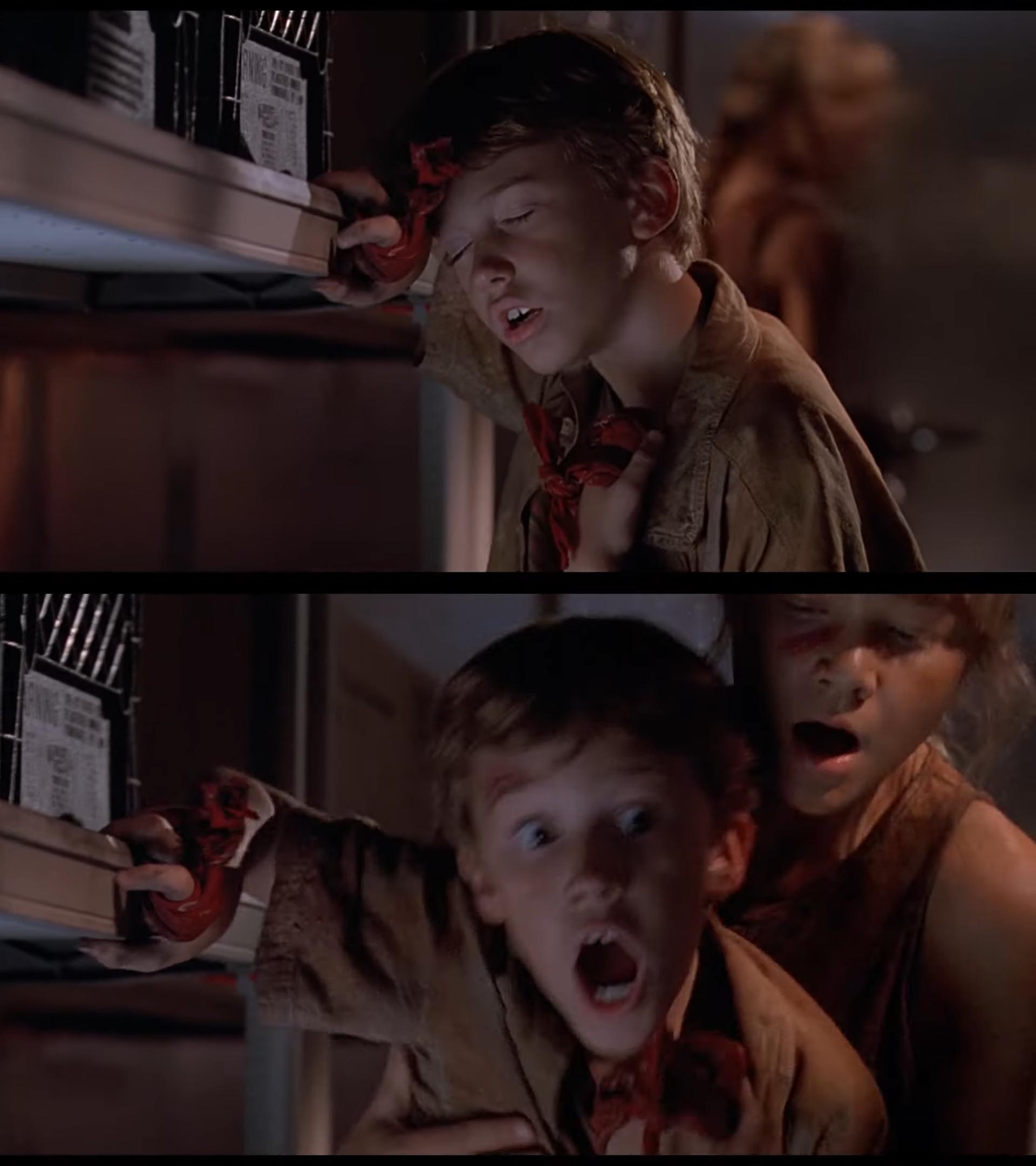

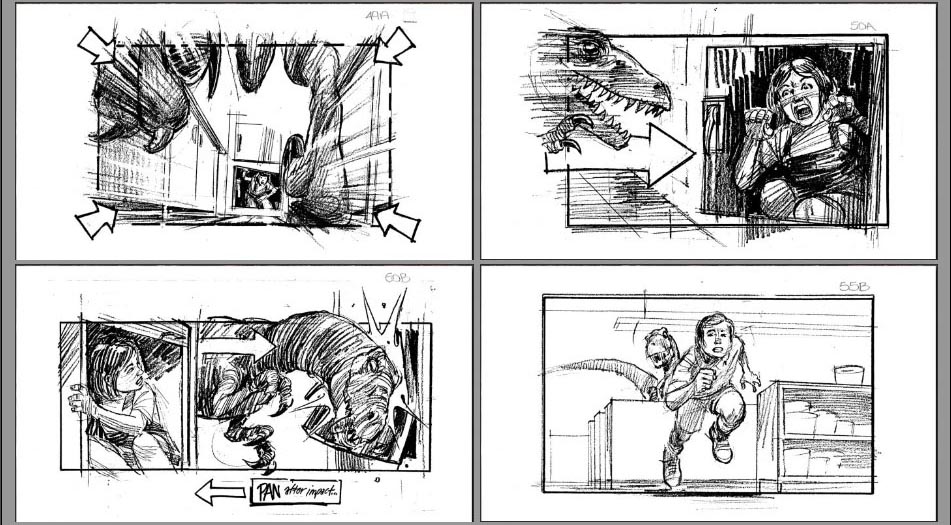

In honor of Halloween, and to see if I could pick out some examples of the “L System” myself, I thought I’d dig into one of the most terrifying scenes from Spielberg’s blockbuster creature feature Jurassic Park. In the scene we find Lex and Tim, the owner of Jurassic Park’s grandchildren, trying to escape two velociraptors as they sneak through the park’s commercial kitchen. Picking up at the climax of the scene, Tim sprints forward, towards the camera, reaching for a large metal door with a bloodthirsty velociraptor trailing close behind. Tim attempts to slam the door behind him but the velociraptor jams its head through the crack, snapping back at him and keeping the door open. This all happens in one continuous shot that keeps the subjects, the location, and the actions clear.

Cut to Lex already in the room and running toward the door with arms outstretched, the camera moving with her from left to right.

Using her momentum, she helps Tim close the door, followed by a few quick close-up shots of her turning the key and securing the lock.

The camera pivots back to Tim, trying to catch his breath. The camera moves forward, pushing in on our subject. Lex, out of focus in the background, moves toward Tim in frame, before grabbing him by surprise as she comes into focus.

The camera pivots back to Tim, trying to catch his breath. The camera moves forward, pushing in on our subject. Lex, out of focus in the background, moves toward Tim in frame, before grabbing him by surprise as she comes into focus.

We then get the perspective of one of the velociraptors in an over the shoulder shot, peering down on Lex and Tim, hand in hand, running from the left of the screen to right. Our distance from the children and the relative stillness of the camera denotes temporary safety for the children as they flee.

The scene is punctuated with one last shot. A quick push-in close-up of the velociraptor growling and sneering after a failed hunt.

The scene is punctuated with one last shot. A quick push-in close-up of the velociraptor growling and sneering after a failed hunt.

This action scene is set in a dimly lit and confined indoor space with child actors working opposite creatures cobbled together with animatronics, puppetry, and CG. The fact that this works as well as it does is a minor miracle and a testament to good planning and solid artistic direction. Thirty years later and it still looks incredible.

You can find storyboard artwork of this scene and others from Jurassic Park over at the fan site Jurassic World Universe.

I wasn’t familiar with Steven Spielberg’s lifelong interest in video games until I read Bob Mackey’s book on Day of the Tentacle put out by Boss Fight Books in October of last year. Peter McConnell, the composer for many LucasArts games and beyond, mentions Spielberg as he discusses the difficulties you’d run into programming a game for both high-end and low-end computers:

I wasn’t familiar with Steven Spielberg’s lifelong interest in video games until I read Bob Mackey’s book on Day of the Tentacle put out by Boss Fight Books in October of last year. Peter McConnell, the composer for many LucasArts games and beyond, mentions Spielberg as he discusses the difficulties you’d run into programming a game for both high-end and low-end computers:

One of our biggest fans was Steven Spielberg, and every time we’d do a LucasArts game, we’d get a letter from Steven Spielberg saying how much he loved what we did, which was very fun. And Steven had – I hope you don’t mind I call him Steven, I never met him – he had a full time guy who kept his game computer. At least this was reputed to be true.

And so, he had the guy who kept his gaming computer system up to scratch, so I’m sure he had the fastest PC and a killer surround sound system, and a great room to play in. So, we were basically creating games for everybody from Steven Spielberg to play to some college kid who’s got a PCAT that they found in a dumpster, and has not even a SoundBlaster but just an AdLib card.

And so, he had the guy who kept his gaming computer system up to scratch, so I’m sure he had the fastest PC and a killer surround sound system, and a great room to play in. So, we were basically creating games for everybody from Steven Spielberg to play to some college kid who’s got a PCAT that they found in a dumpster, and has not even a SoundBlaster but just an AdLib card.

In 1992, Ed Bradley conducted a 60 Minutes interview with Spielberg at his Amblin Entertainment office complex on the Universal Studios back lot.

Early on in the clip, they take a detour to highlight some of the arcade cabinets that line his office. Bradley describes Spielberg as a “grown-up kid” with “adult toys.”

For decades, Spielberg has been involved in the video game landscape, from conceiving the point-and-click adventure game The Dig (1995) to creating the Medal of Honor series inspired by his experience making Saving Private Ryan (1998). He even had an office at EA’s headquarters in the late 2000s where he designed and released the puzzle/action games Boom Blox (2008) and Boom Blox Bash Party (2009) for the Nintendo Wii.

But is Steven Spielberg still playing video games in 2024? According to his son Max, yes he is.

For decades, Spielberg has been involved in the video game landscape, from conceiving the point-and-click adventure game The Dig (1995) to creating the Medal of Honor series inspired by his experience making Saving Private Ryan (1998). He even had an office at EA’s headquarters in the late 2000s where he designed and released the puzzle/action games Boom Blox (2008) and Boom Blox Bash Party (2009) for the Nintendo Wii.

But is Steven Spielberg still playing video games in 2024? According to his son Max, yes he is.

He loves gaming. He’s the one who got me into it, like, he plays games. He’s a big PC gamer, and so that’s kind of our bonding point as well. You know, he’s like ‘what’s good? Which Call of Duty should I be playing? Just send me a list of the top five shooters and I’ll get them downloaded and then we can play them together when you come over to the house.’

He’s big into story games and I’m always trying to get him to play Uncharted, because I’m like ‘hey, it’s Indiana Jones, you’d appreciate this’ and he’s like ‘I can’t do controllers, I can only do keyboard and mouse.’

But he also plays a lot of mobile games so he’s big into Golf Clash and things like that too. Anything he can pull out and play on the side.

He’s big into story games and I’m always trying to get him to play Uncharted, because I’m like ‘hey, it’s Indiana Jones, you’d appreciate this’ and he’s like ‘I can’t do controllers, I can only do keyboard and mouse.’

But he also plays a lot of mobile games so he’s big into Golf Clash and things like that too. Anything he can pull out and play on the side.

Last month Ben Hanson of MinnMax interviewed Max Spielberg who has been working in the AAA-space of the video game industry for nearly two decades and is the Co-Founder (along with Tatyana Dyshlova) and Creative Director of the new independent development studio FuzzyBot. Eric Kozlowsky, FuzzyBot’s Art Director, joined Max for the interview to talk about the studio’s first game Lynked: Banner of the Spark (pitched as Hades meets Animal Crossing), which just released on Steam in Early Access last week.

In the interview, the two outline their experience working for larger studios, the long path that led them to work at an independent studio, the development of the studio’s first release, and the importance of visual clarity. Kozlowsky explains the importance of this design philosophy and how integral it was to focus on while crafting their action game:

One of our big mandates from Max and the designers was, you know, clear the clutter, clear the noise; we want to make sure that people can see the action and what’s going on. A lot of these games get very noisy very quickly and we’ve tried very hard to maintain this very clear readability that you can see your character, you can see the actions that you’re doing, and the art is there to support that, not take away from it.

Large-scale video games, like feature films, are a collaborative effort. They may be helmed by big-name directors with a history of success, but so much of what is accomplished at such a large scale is possible due to large teams of thoughtful and hardworking individuals. That is to say, if I’d like you to take away anything from this newsletter it’s that you can get a lot out of strong, simple design principles, and being able to share your passions with loved ones is a wonderful thing.

This marks my 12th monthly newsletter, cataloging a full year of Sad Land development and all that comes with it. Although I’m sure the process might seem slow on the outside, I’ve moved the needle quite a bit on the game despite some patches of burnout and restructuring, I’m just as committed as ever to the game and sharing my progress and ideas through this newsletter.

Happy Halloween,

Neil

Happy Halloween,

Neil