Originally published on January 31, 2025

Every January the design podcast 99% Invisible releases an episode of what they call mini stories. These are stories that were either cut for time or topics that seemed interesting to the staff but didn't quite have the depth to warrant producing a full-length episode. As I've been writing this newsletter month by month, I often overwrite or find myself removing tangents that veer too far off topic. I thought it would be fun to pay homage to 99% Invisible and dig up some discarded writing from the past year, flesh it out, and share it with you here.

Marioland Resort

Image retrieved from vg247.com

In my August newsletter, I dove into theme-park design philosophy and its shared commonalities with video game design philosophies. One thing I cut for length was how the developers of the Mario series drew from Disney's park design as it took shape through the late 80s into the 90s. In the book Super Mario Bros. 3 by Alyse Knorr, Knorr writes about the development teams alleged trip to Disneyland in the late 80's:

…a handful of game historians have suggested that SMB3's themed worlds and levels were inspired by a trip that Miyamoto and several members of Nintendo's R&D4 team allegedly took to Disneyland in 1987. It's not a totally crazy idea— SMB3 and the Mario games that followed it (especially SMW and SM64) do feel, in many ways, like theme parks with small worlds inside of them to explore. Each world, like each of the distinct lands at Disneyland, has a unique visual theme and mood created by its music, landscape, map, aesthetic, and castles— which often beat a striking similarity to Cinderella's castle at the center of Disneyland.

To be pedantic for a moment, it's Sleeping Beauty's castle in Disneyland, but this confusion illustrates that this style of castle is a cultural archetype more than a specific castle. Cinderella's castle is in the Magic Kingdom in Disney World but they're functionally the same castle. Super Mario Bros. 3 introduced to the Mario series both a broad selection of distinct biomes and those white European-style castles.

This style of castle became a mainstay in the series and is most prominent in Super Mario 64 as the game's central hub.

Image retrieved from games radar

Following the release of Super Mario Bros. 3, Super Mario Land (produced by Nintendo R&D1, the team behind Metroid and Kid Icarus) was released for the Game Boy in 1989 and Super Mario World (produced by Nintendo R&D4, the team behind all previous Super Mario titles) on the SNES in 1990. Both were launch titles for their respective systems and both follow a similar naming convention to Disney's North American parks – Land for the smaller experience and World for the main course.

Image retrieved from mariouniverse.com

Super Mario Bros. 3 may have been the first game in the series with level-select maps and explicitly themed areas, but Super Mario World was the first game in the series to connect them all in a sprawling overworld map.

Image retrieved from mariouniverse.com

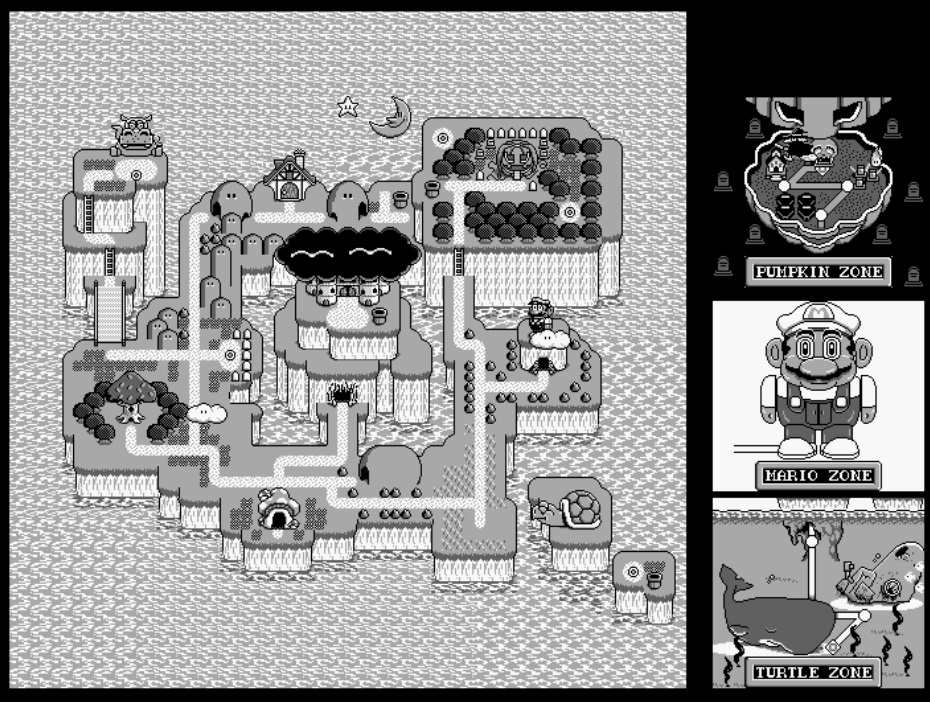

Super Mario Land 2: 6 Golden Coins, the sequel to Super Mario Land, came to the Game Boy a few years later with maybe the most explicitly theme-parky map design to grace a Mario game. It's playful, it's creative, and it even has a Mario zone, likely a playful nod to Mario evolving into a mascot rivaling Mickey Mouse himself.

Image retrieved from mariowiki.com

In 2002 we got the tropical Pinna Park in Super Mario Sunshine – complete with a rideable rollercoaster and a scalable Ferris wheel.

Image retrieved from Wikipedia

And finally in 2021, bringing it all full circle, Japan's Super Nintendo World opened to the general public.

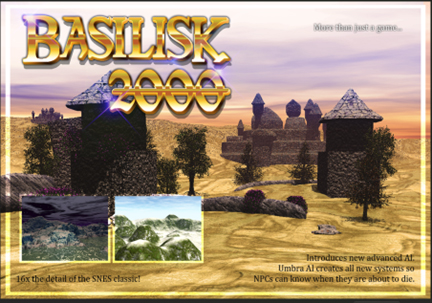

A Real Fake Game

My September newsletter on fake video games was running so long that I remember joking with my wife that I could start a second newsletter just writing about fake games from The Simpsons. The most interesting thing I regret cutting was a writeup about Basilisk 2000, an indie game I first heard about on the No Clip Crewcast. It is truly unlike anything I've ever played.

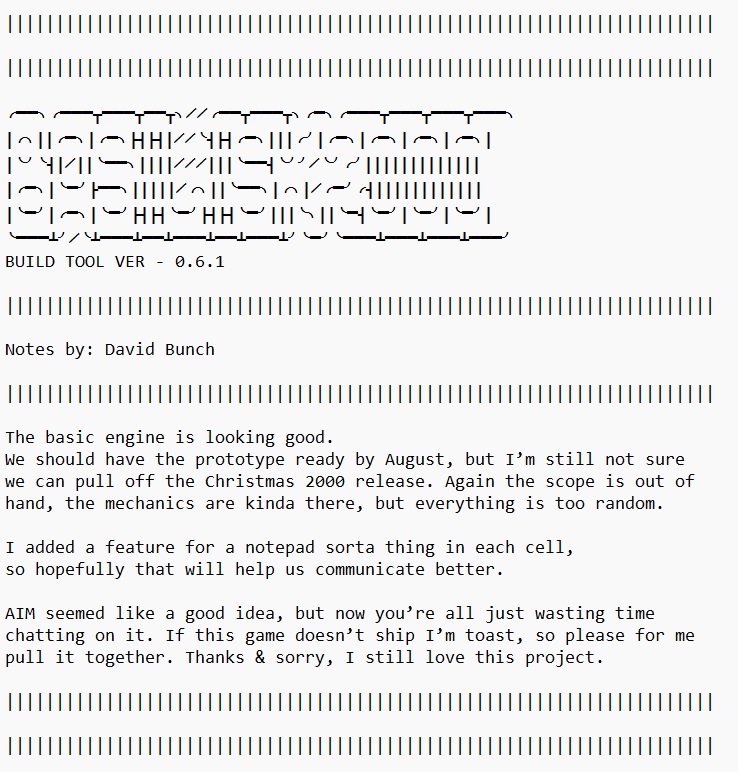

I first purchased the game from the developer KIRA's itcho.io page and downloaded the zip file to my computer. The game folder includes an exe file titled ‘Basilisk 2000 Build Tool', a slew of assets files, and an accompanying README file. For those who are unfamiliar, a program's README file is a plain text document that usually outlines basic information about the program and functionality. In some ways it acts like a book's front matter.

Basilisk 2000's README file, if you are curious enough to click on it, provides the first bit of metafiction, supplying context for the program you're about to boot.

Basilisk 2000's README file, if you are curious enough to click on it, provides the first bit of metafiction, supplying context for the program you're about to boot.

The premise of the game is that you are rooting though the development environment of an old, unreleased game. Further down in the README file is an addendum written by one Kyle Tubman on 10/1/2020 giving an update on how they got lucky finding a working version of the game on eBay and proceeded to wrap the file in the Unity game engine so that others can “explore what would've been.”

Initially, there's not much you can do once the game loads, but the NOTES section hints that you start in HAVENWOOD. If you type LOAD HAVENWOOD into the command prompt and press enter, you'll be dropped into the starting town.

A few NPCs populate Havenwood, unpolished and unmoving. Smoke billows from a chimney in Havenwood but the birds hang in midair. Those assets are designed but were never animated. Clicking on the boot icon to the left of the viewfinder unlocks the ability to walk around and explore the muddy-colored play space. There's an emotional discomfort interacting with the space, like reading someone else's journal or exploring someone's room without explicit permission.

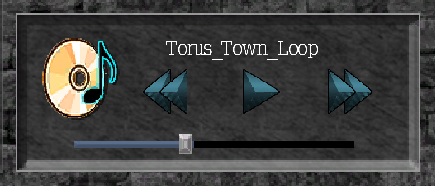

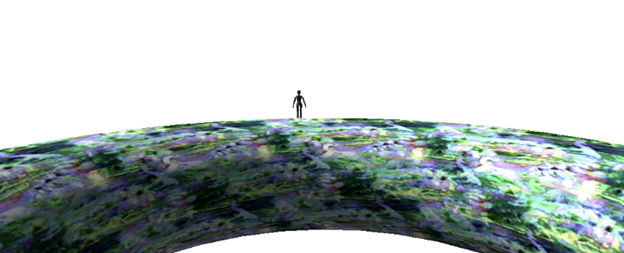

In the center of the screen is a simple audio player. You can play the music and cycle through the tracks. One track you can listen to is called Torus_Town_Loop. If you can load Havenwood, it stands to reason that you can load Torus Town as well. Typing LOAD TORUS TOWN doesn't work. But if you try LOAD TORUS, a popup window appears.

Where does it send you? Well, when the level loads, the player character teleports to a giant multi-colored donut in a white void. On the other side of the donut is the silhouette of an NPC. The haunting drone of the Torus_Town_Loop audio file sets an uneasy tone.

In the bottom-right of the screen is a list of Local Items. The only item listed is NPC_DAVID. David does not move, but you can walk closer if you'd like.

Beyond digging into the lore of the game's narrative and metanarrative, there are some interesting things that you can access within the game's documents. For instance, there is an image file of some promo art (shown above) as well as an unusable .SMC file. In the game's lore, there is another unreleased game produced for the Super Nintendo. Files with .SMC extensions are Super Nintendo rom files which you might know if you've ever used an SNES emulator. SMC is short for Super Magicon, the original working title for the Super Nintendo. It's a detail I really appreciate.

Midnight Release

As I was gathering research for topics to write about, I turned to my bookshelf for inspiration and picked out The Art of Invader Zim. Invader Zim was a short-lived Nickelodeon series about an alien invader, Zim, covertly living among humans with the intent of taking over earth in the name of his home planet.

Gaz, the misanthropic sister of the boy fighting to stop Zim from taking over the planet, is often seen playing her portable console, the Game Slave. In the first season of the show, the episode Game Slave 2 follows Gaz to the mall, waiting in line for the midnight release of the new console. I bring this up here because throughout 90s media it was uncommon for video games to be presented accurately or positively. Nickelodeon's Doug had an episode about Doug going on a video game bender when he wins a Super Pretendo (remember kids, everything in moderation). Throughout The Simpsons first decade, it often only gave us a glimpse of gaming as it was in the 80s, mindlessly pumping quarters into big arcade cabinets. I'm sure there are counterexamples I'm glossing over, but generally video games were presented as a juvenile hobby for young boys.

Invader Zim's Game Slave 2 sits at a turning point in video game representation in pop culture. Writer's rooms in the 90s were filled with adults who had grown up on Atari and Donkey Kong. By the early 2000s, younger television writers had watched games evolve as children and teenagers and they wrote about the topic from a more nuanced and personal perspective. Additionally, video games were becoming less niche. This was the era of playing The Sims in the living room on the family computer, of hooking up multiple Xbox consoles in a college dorm room to play 16-player Halo deathmatch, of buying a PlayStation 2 because it played DVDs when most people didn't have a DVD player. The next generation of consoles were rolling out and that brought with it the excitement of the midnight release. Invader Zim wasn't alone in depicting one of these releases. Just a few months earlier the plot of a South Park episode hinged on the midnight release for their own fantasy console, the Okama Gamesphere.

Invader Zim's Game Slave 2 sits at a turning point in video game representation in pop culture. Writer's rooms in the 90s were filled with adults who had grown up on Atari and Donkey Kong. By the early 2000s, younger television writers had watched games evolve as children and teenagers and they wrote about the topic from a more nuanced and personal perspective. Additionally, video games were becoming less niche. This was the era of playing The Sims in the living room on the family computer, of hooking up multiple Xbox consoles in a college dorm room to play 16-player Halo deathmatch, of buying a PlayStation 2 because it played DVDs when most people didn't have a DVD player. The next generation of consoles were rolling out and that brought with it the excitement of the midnight release. Invader Zim wasn't alone in depicting one of these releases. Just a few months earlier the plot of a South Park episode hinged on the midnight release for their own fantasy console, the Okama Gamesphere.

Gaz playing Vampire Piggy Hunter on her Game Slave

The Art of Invader Zim book didn't have anything all that interesting to say about the episode Game Slave 2 so I was curious if the show's commentary track held anything interesting. In 2007, I lent out my DVD set of Invader Zim to a coworker when I was working at Rite Aid and never got them back so I scoped around online to see if I could find an .ISO of the DVD with the episode's commentary. After an hour or so of work finding and downloading the file, I booted up the episode in VLC, only to find that there wasn't much insight. All anyone had to say about video games was Roman Dirge, credited with coming up for the story for the episode - with Eric Trueheart as the main writer. Dirge says, "We all love video games so much in our little group that it had to be done." That's it. I don't know what I was expecting but I was initially disheartened he didn't have more to say. Looking back on it now, I actually find this to be a sweet sentiment. The episode was a love letter to a shared passion among the writers. It's as simple as that.

Blink and You'll Miss It

At the end of last year, I finally played through the game Before Your Eyes. It's a short narrative game where you play as a character named Ben recounting the story of his life through a series of vignettes. A scene from Ben's life will play out – a piano lesson, a playdate with the neighbor kid, a sick day in bed – but when you get to the end of the sequence, if you blink the scene will cut short, moving you forward in time. Before you start, you must calibrate your computer's camera to make sure it can register when you blink your eyes. The main mechanic is not tied to a controller, it's just you and the game.

There's something about this style that allows you to fully engross yourself in Before Your Eyes, making it a strange and intimate experience. There's a tenderness to the story, a sadness to blinking too soon and cutting off a line of dialogue, a beauty to life's spectacle and life's mundanity as depicted in the game. You fight your body's instinct to close your eyes so that you can linger on a sunset for just a moment longer. When you raise your eyelids, you don't know how much time will have passed. A week? A month? A year?

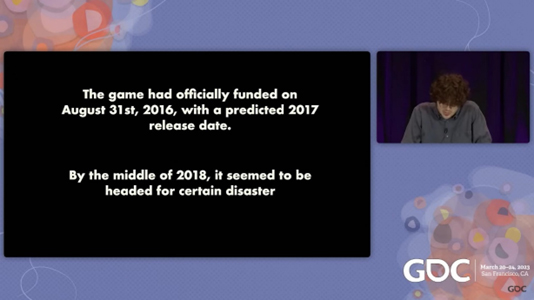

The game's writer and creative director Graham Parkes gave an excellent talk at GDC's 2023 Game Narrative Summit titled Learning From Loss: Designing the Experimental Narrative of 'Before Your Eyes'. Here Parkes discusses the difficulty the team had finishing the game:

And the months passed into years, the game became a kind of real source of stress for me and I think for the whole team. I mean, I'll only speak for myself, you know I'd be out at dinner and a family member or friend would “hey, what happened to that game I gave forty bucks to, you know, two years ago.”

It felt like a real impossible situation. Because, on one hand, we all knew what we were doing wasn't working and our lives and mental health would definitely be better if we just abandoned it, but we also had too much pride and, you know, we still somewhere really did believe in this game, we just had no idea how to make it.

Having played the game, it feels inevitable and complete, the way art always does when it hits right. But hearing him talk about the long, meandering production was a reminder that no art is inevitable. Art takes effort, revision, collaboration, and time.

And the months passed into years, the game became a kind of real source of stress for me and I think for the whole team. I mean, I'll only speak for myself, you know I'd be out at dinner and a family member or friend would “hey, what happened to that game I gave forty bucks to, you know, two years ago.”

It felt like a real impossible situation. Because, on one hand, we all knew what we were doing wasn't working and our lives and mental health would definitely be better if we just abandoned it, but we also had too much pride and, you know, we still somewhere really did believe in this game, we just had no idea how to make it.

Having played the game, it feels inevitable and complete, the way art always does when it hits right. But hearing him talk about the long, meandering production was a reminder that no art is inevitable. Art takes effort, revision, collaboration, and time.

Just last week Maddy Thorson posted an update on Extremely OK Games, Ltd.'s website with the header Final Earthblade Update. Thorson is a developer I've brought up in my newsletter in the past. She wrote, directed, and designed Celeste, a 2018 indie game heralded for its design, narrative, and excellent precision platforming. First announced in 2019, Earthblade was meant to be the studio's next game, a sprawling pixelated exploration-focused platformer, but due to personal reasons outlined in the update, the game has been cancelled. It's very sad news to read and sounds heartbreaking for all involved. It takes courage to leave something behind after half a decade's worth of work and it takes courage to be as open as Thorson has been. I'm sure I would have loved Earthblade but I am standing by to see what the studio does next once they're ready.

I've spent the month of January developing a new feature for Sad Land that I'm excited to share. The next newsletter will outline my journey mapping out and iterating through the process. It's silly, it's fun, and it's something I think will help flesh out the gameplay experience. I also finished a second draft of a short story that should be released in some shape or form within the first half of this year. Rest assured, you'll be the first to hear about it once there is news to share!

Sincerely,

Neil

Sincerely,

Neil