Originally published on February 21, 2025

I’ve been reading through Steve Swink’s Game Feel: A Game Designer’s Guide to Virtual Sensation after years of hearing it recommended time and time again. As someone who’s been exploring the topic of game design for years, it’s a fascinating academic read and has got me thinking more about how players engage with games and how games react back to the player.

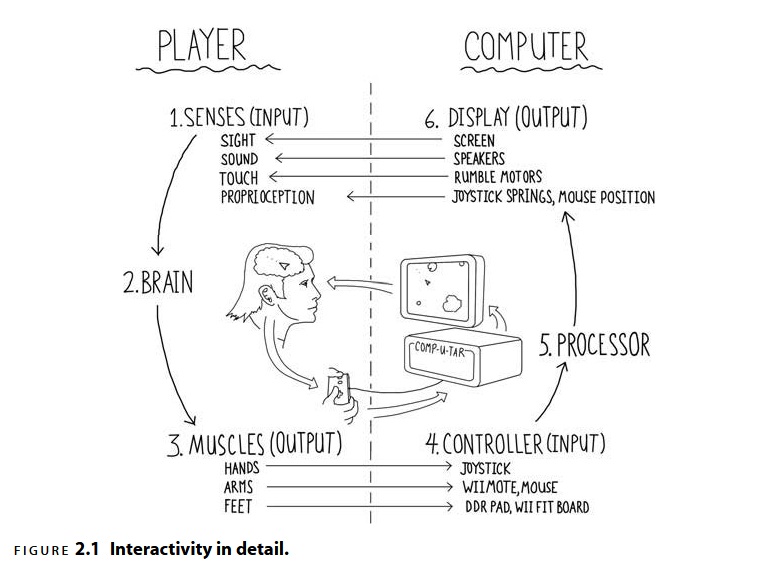

In Game Feel, Swink explores these ideas on a granular level. It can be a fairly dense read, but sprinkled throughout are digestible illustrations like the one below that lays out a six-step interaction cycle, breaking down the physical and mental dance between player and game.

From the chapter Game Feel and Human Perception from Swink’s book Game Feel

1. SENSES (INPUT) - The player perceives the screen.

2. BRAIN - The player processes this information and decides what action to take.

3. MUSCLES (OUTPUT) - The player physically reacts to the stimulus by interacting with the controller.

4. CONTROLLER (INPUT) - The controller input is received by the computer.

5. PROCESSER - The computer processes the input.

6. DISPLAY (OUTPUT) - The output on the screen adjusts to supply updated feedback.

So, there is this cycle happening on both sides: receive stimulus, process stimulus, react to stimulus. Swink claims that the player, on average, can physically react once every 240 milliseconds (ms), meaning a human can react to a video game several times a second. The computer, on the other hand, refreshes dozens of times a second. Many modern games can run up to and exceeding 60 frames per second (fps), which means the computer is processing and refreshing its display at that speed. If the processors are trying to make too many calculations at once, the frame rate will slow down, resulting in a choppy or stuttering display.

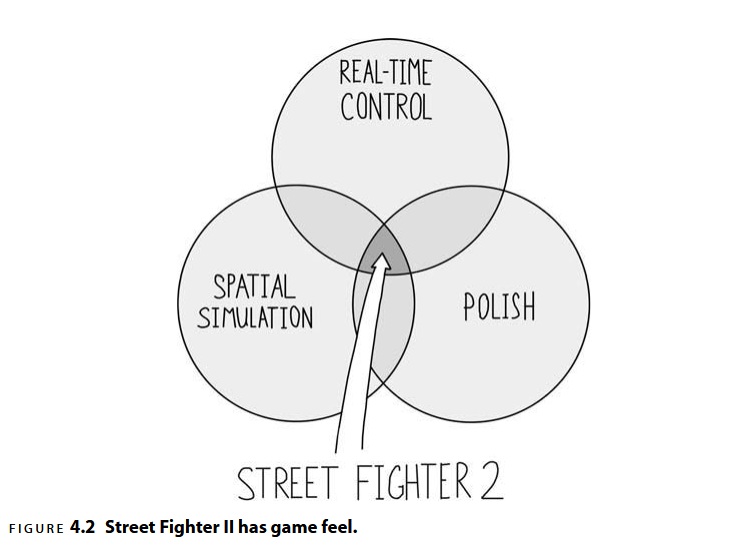

If you’ve seen any footage of Sad Land, it’s clear that Sad Land is a slow game and actually doesn’t contain any “game feel” as Swink defines it in his book - the combined experience of real-time control, simulated space, and polish. Slime walks on a rigid grid, meaning there are no controls within the play space to master and no physics engine to perceive in real time.

Although Sad Land doesn’t currently have any mechanics that constitute game feel, reading the book has got me thinking about adding some mini-games that temporarily give the player more physical agency. My end goal is not to make Sad Land an action-oriented game, but a less predictable game with a diverse range of game-play styles sprinkled throughout. I have a few interactions planned, but there is one I’ve nearly completed and wanted to explore how I approached building this interaction here in the newsletter.

Within the first area of the game, the castle, I have a gang of dark blobs labeled as “kids” within the game’s files. They’ve been part of the project for over a year, which means they’ve been sitting in my head for that whole time. I recently watched an interview with the late, great David Lynch where he discussed the long, drawn-out production of Eraserhead. Over the film’s five-year production, Lynch would shoot a scene, stop production, and then seek further funding to shoot the next scene. He claims in the interview that there are benefits to working in this way: “There’s also something good about staying in a film for a certain amount of time because you sort of sink deeper into it.” I love the way he expresses this, as it’s something I’ve felt with projects time and time again. Sure, there are benefits to building things quickly, but the ideas that gestate in the brain as it works slowly over months and years are unique to this process. So, these kids, this silly gang of sprites, have personalities and desires that have organically grown since before I even crafted their image files. And I know intuitively that they love dancing, so that became the first simple mini-game.

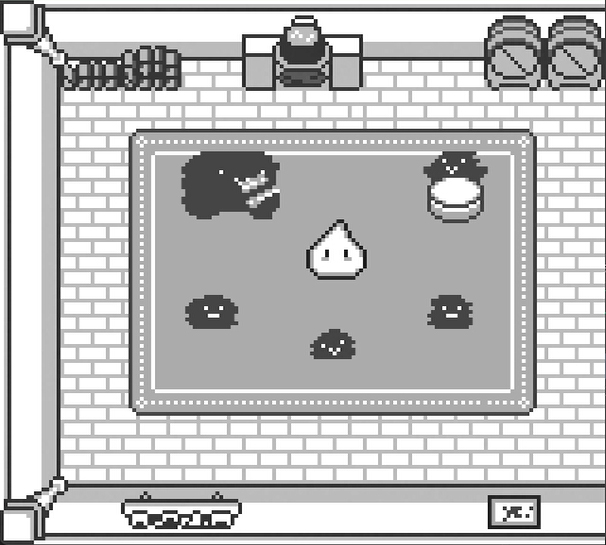

This optional interaction would come after meeting them and after their part in the quest line is complete. If you approach them, they will ask you if you’d like to play the dancing game. They call it a game in the way little kids call any structured activity a “game.” If you say yes, the screen goes dark and when it fades back in, your slime character is at the center of the screen surrounded by the kids. A few are playing instruments while others stand around you, ready to dance.

This optional interaction would come after meeting them and after their part in the quest line is complete. If you approach them, they will ask you if you’d like to play the dancing game. They call it a game in the way little kids call any structured activity a “game.” If you say yes, the screen goes dark and when it fades back in, your slime character is at the center of the screen surrounded by the kids. A few are playing instruments while others stand around you, ready to dance.

This game interaction is inspired in part by a mini-game from Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Ages where you are asked to memorize the movements of a dancing goron. They perform a sequence of moves and you must repeat them exactly, similar to the game Simon. For Sad Land, I want something less stressful and more easy-going, so instead of following the computer’s movements, you dance and they follow your lead.

The kids were inspired by the Susuwatari (“wandering soot”) appear in My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away. The characters in Sad Land are verbal, much larger, and have their own kitchen.

Before getting to work on implementing this in Game Maker, I imagined the simplest version of the sequence and what inputs and limits I would set for player interaction. To start, I would need rough visuals for the player character, a simple, functioning metronome, and the little creatures who would follow your movements. Next, I would need to code a sequencer that would keep the time and trigger any sounds as needed. Finally, I would need to tie everything together with directional inputs and a key logger (a coded function that would save each player input), giving the player the ability to supply a sequence of directional inputs and for the game to have the ability to react back.

The first version of this project looks rough but having a simple and tested initial proof of concept is important to know what visuals to produce for the final version and what technical aspects might cause trouble along the way. In this case, it was clear that sequencing a drum pattern with coinciding animations would be the most trivial aspect but my experience with digital music production would at least give me some foundation to work from.

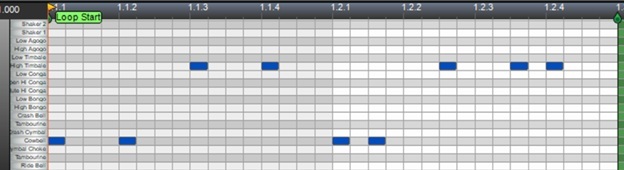

The next step I took was to add polish to the visuals and add some complexity to the rhythm. In my initial test, I kept it very simple by triggering only one drum sample at the very beginning of the loop. To add some complexity and playfulness to the drum loop, I decided to implement a simplified bossa nova-style rhythm.

After some research and playing around in Mixcraft (my digital audio workstation of choice), I mapped out a two-percussion loop that I could implement within the code I’d already written for the project.'

For the percussion, I picked two preexisting characters and two percussion instruments (the clave and the drum) and then got to work on animating their movement.

For the percussion, I picked two preexisting characters and two percussion instruments (the clave and the drum) and then got to work on animating their movement.

Some design iterations of Mico, first playing the wood block before switching the instrument to the clave and then getting the size right.

If I was using more complex assets, I would absolutely keep the visuals for last, but one of the benefits of designing a game with chunky pixels is that they are fairly simple to lay out.

With the music and input working well enough, I added a background to get an idea of what a final version of this interaction would look like within the game itself.

The final step will be to engineer some Game Boy sounds to replace the placeholder sounds used for testing. For now, you can find a video of my working prototype HERE. As I work to build out more slices of Sad Land, I plan to present them here in the newsletter to show how the iterative design process works. The player may be able to react to a game within 240 milliseconds, but laying the track of those experiences takes time to construct.

I’m sending this newsletter out earlier than usual because I’ll be on vacation for the rest of the month. I’ll be flying down to Orlando tomorrow to spend a full week at Disney World. This winter has been especially cold in New England and a bit of sun and escapism is just what I need right now to fill up my cup. I currently don’t have any plans to write about my trip but I’m sure it’ll worm its way into a future newsletter.

Sincerely,

Neil