Originally published on Dec 30, 2023

Season’s greetings!

In the last newsletter, I explored how I go about crafting authentic Game Boy chiptune sounds for my game Sad Land (demo still in development). For this month’s newsletter, I’ll be documenting how I stick to the visual limitations of the Game Boy.

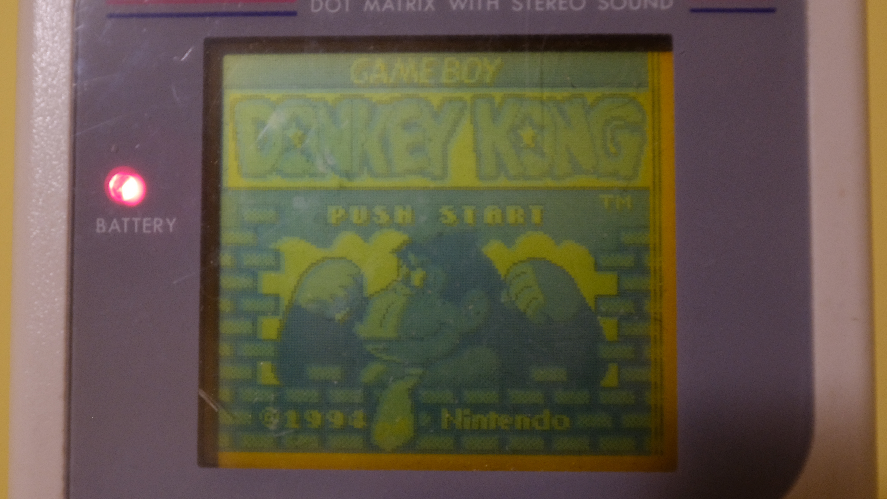

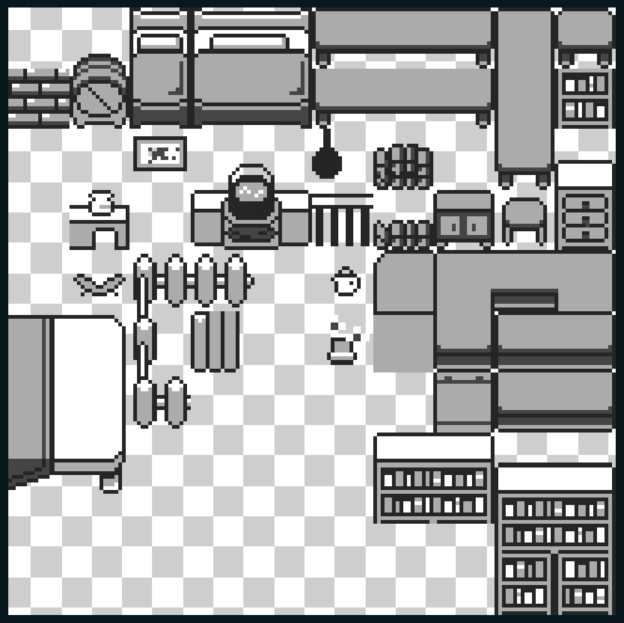

Below is a picture of the original Game Boy display. The screen itself doesn’t have any built-in light so it was actually pretty tricky to get a decent shot of it in action. As you can imagine, it’s hard to see the screen properly unless you are outside or sitting under a lamp, but similar to watching movies with subtitles, you acclimate to it fairly quickly and, after a few minutes, dissolve into the experience.

In the last newsletter, I explored how I go about crafting authentic Game Boy chiptune sounds for my game Sad Land (demo still in development). For this month’s newsletter, I’ll be documenting how I stick to the visual limitations of the Game Boy.

Below is a picture of the original Game Boy display. The screen itself doesn’t have any built-in light so it was actually pretty tricky to get a decent shot of it in action. As you can imagine, it’s hard to see the screen properly unless you are outside or sitting under a lamp, but similar to watching movies with subtitles, you acclimate to it fairly quickly and, after a few minutes, dissolve into the experience.

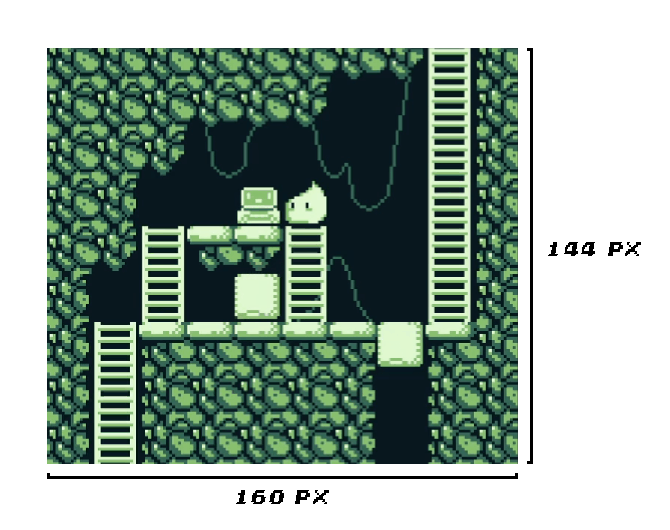

The display for the console is a small 160 pixels wide by 144 pixels tall.

To put those dimensions in perspective, if I didn’t scale/enlarge the game display on my computer (1920 pixels by 1080 pixels or ‘HD resolution‘), it would look like this…

Beyond the small resolution, the other main constraint working with this visual style is the color palette. The Game Boy displays 4 colors: white, black, and two shades of gray. The original Game Boy screens have a green tint to them, which, from what I understand, is a byproduct of the hardware itself and not any Game Boy game's designed color scheme.

I won’t get into the weeds about how different Game Boys display games in different ways here, but I can show you that the same game playing on the Game Boy Advance SP [2003] has a color palette tailored to the game itself. So the color and size of the screen can vary among different models.

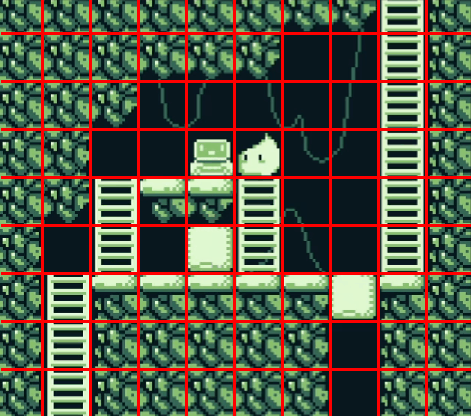

When laying out graphics on the Game Boy hardware (and the Game Maker software I’m using to build Sad Land), they would use tilesheets. These are larger image files containing smaller square 8 x 8 images or 16 x 16 depending on the level of detail. Most all of the visual assets I build out for Sad Land use tilesheets. Some assets are one time use, some are made to reuse again and again. The brick pattern in the top-left of the image below can be used as a pattern for an entire brick walkway, for example.

The actual Game Boy hardware has very specific limitations on how many of these unique sprites it can display at any given time. When laying out the art in Sad Land, I have more freedom than I would have if I were programming the game for the Game Boy hardware itself. Programming a game is hard enough without having to adhere to the archaic Video RAM limits of over 35-year-old hardware.

Below is an example of how I might view a single screen area in the game. The grid of 16 x 16 squares gives me a guide to lay out the walls and details of the space. The slime too is 16 x 16 and moves incrementally through this grid.

Below is an example of how I might view a single screen area in the game. The grid of 16 x 16 squares gives me a guide to lay out the walls and details of the space. The slime too is 16 x 16 and moves incrementally through this grid.

From the moment I conceived of the game, I wanted to roughly stick to the limitations of the Game Boy, if not just to keep the scope of the game reasonable. Without clear limitations on a project from the beginning (both technical and story), these types of projects can balloon to the point that they never get finished. My next project won’t be so limiting but for Sad Land, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

THE NINTENDO GAME BOY: THE LITTLE HANDHELD THAT COULD

The Game Boy’s display was modest technology even for its time. The Game Boy was released in 1989, the same year Atari put out their own handheld console, the Atari Lynx, with Sega releasing their portable Game Gear the following year in 1990. Both of the Game Boy’s main competitors had backlit color displays and more capable hardware, which you’d think would give them the advantage, but the Game Boy outsold them both by a large margin. With a simpler processor and a display closer to a calculator than a television (legend has it that the Game Boy’s designer Gunpei Yokoi was inspired to build the Game Boy after seeing a businessman playing with a calculator on his commute), the battery life for the handheld was incredible. It can run for up to 20 hours on 4 AA batteries. The Game Gear and Atari Lynx, in comparison, take 6 AA batteries with 3-5 hours of battery life.

The other day, while reading through Gabe Durham's book on Bible Adventures for the NES (a fascinating book about unlicensed Christian-themed Nintendo games programmed almost exclusively by atheists/agnostics), I came across a small section about the Atari Lynx. Dan Burke, one of the developers on Crystal Mines II for the Atari Lynx, described the Lynx as "orphan hardware that's in the annals of history but not a lot of people had it at the time." I don't hear about the Lynx very often, so I found it serendipitous to stumble upon this quote in the midst of doing research for this newsletter. It also reinforces my memory of the handheld market at the time, in which Sega's Game Gear was really the Game Boy's only competition but even then it never came close to usurping the Game Boy's foothold on the industry.

I sought out this 1991 Toys R US catalog (credit to AUSRETROGAMER, CLICK HERE to see their writeup) to give you an idea of how they looked advertised side-by-side. The NEC Turbo Express isn’t a console I’m familiar with so I didn’t mention it above but it’s clear that such an expensive handheld would have been a hard sell.

The other day, while reading through Gabe Durham's book on Bible Adventures for the NES (a fascinating book about unlicensed Christian-themed Nintendo games programmed almost exclusively by atheists/agnostics), I came across a small section about the Atari Lynx. Dan Burke, one of the developers on Crystal Mines II for the Atari Lynx, described the Lynx as "orphan hardware that's in the annals of history but not a lot of people had it at the time." I don't hear about the Lynx very often, so I found it serendipitous to stumble upon this quote in the midst of doing research for this newsletter. It also reinforces my memory of the handheld market at the time, in which Sega's Game Gear was really the Game Boy's only competition but even then it never came close to usurping the Game Boy's foothold on the industry.

I sought out this 1991 Toys R US catalog (credit to AUSRETROGAMER, CLICK HERE to see their writeup) to give you an idea of how they looked advertised side-by-side. The NEC Turbo Express isn’t a console I’m familiar with so I didn’t mention it above but it’s clear that such an expensive handheld would have been a hard sell.

Jump ahead to holiday season 1996 (scans courtesy of pwnpocalypse on imgur via Business Insider) and you can see its affordability persisted along with fresh new color options and the introduction of the Game Boy Pocket: weighing almost half as much, taking 2 AAA batteries instead of 4 AA batteries, and a less bulky design.

The console’s staying power and its ubiquity among my gaming cohort is the reason I have nostalgia for it now and the reason why going into 2024, I am crafting a game that harkens back to this era in gaming. The console I played in the living room was the family’s game system. It was a system that shared users and shared the same screen as cable news. The console that fit in my pocket that I played on the bus on the way home from school was mine and mine alone. The Game Boy was quiet and personal and you could play it for a long time without having to ask your parents for more AA batteries. It was a companion.

The Wanderer: Winter Solstice Special

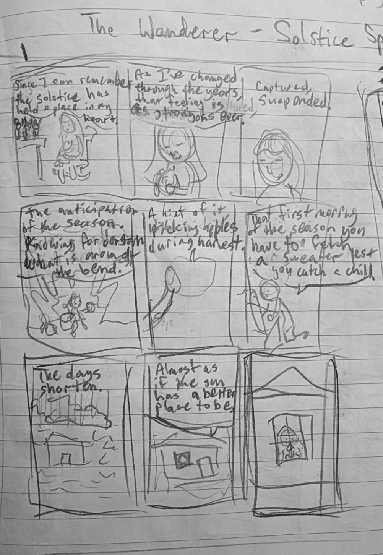

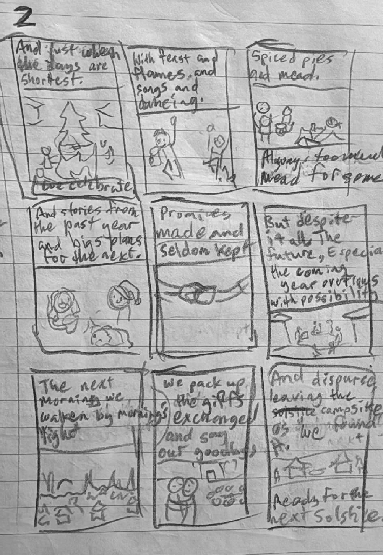

Back in 2021, I was asked by my friend and fellow artist TH Ponders if I wanted to write and help produce a winter holiday special for their podcast, The Wanderer. I agreed to the project and started piecing the story together in August 2021, eventually releasing it in December 2021. I tried scripting the story using several different methods before deciding to thumbnail the entire first draft as a 15-page comic.

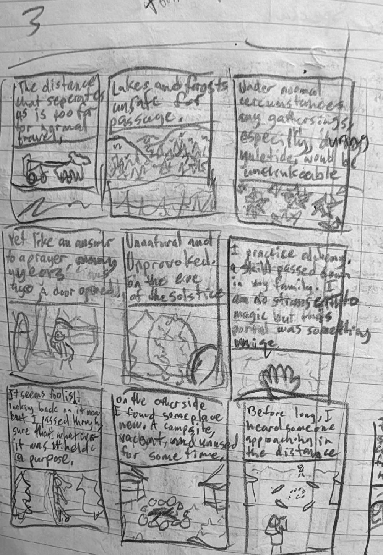

The show's tone is told mostly in monologues with a strong sense of place, so laying out the story visually in a medium I have plenty of experience with made the most sense. I love the 9-panel comic page as it naturally dictates the pacing of the writing process with each row standing in as a beginning, middle, and end respectively.

Below are the first few pages of my first draft...

The show's tone is told mostly in monologues with a strong sense of place, so laying out the story visually in a medium I have plenty of experience with made the most sense. I love the 9-panel comic page as it naturally dictates the pacing of the writing process with each row standing in as a beginning, middle, and end respectively.

Below are the first few pages of my first draft...

...and you can listen to the full episode HERE or you can look it up anywhere you listen to podcasts. Although I recommend listening to the entire series, this episode is a completely standalone experience.

In addition to writing the episode, I also edited, scored, and sound-designed it. It took a lot of work but I am proud of it and hope to do other projects like it down the road.

Hope you have had a restful and relaxing holiday season!

Sincerely,

Neil

In addition to writing the episode, I also edited, scored, and sound-designed it. It took a lot of work but I am proud of it and hope to do other projects like it down the road.

Hope you have had a restful and relaxing holiday season!

Sincerely,

Neil