Originally published on March 31, 2024

Last December, just a week before Christmas, both my wife and I tested positive for Covid. We cancelled our plans, placed an online order for food to tide us over, braced ourselves for an unfortunately pared-down holiday break, and isolated ourselves in our apartment. We spent those evenings in the living room, my wife on the couch and me on our oversized beanbag, watching The Great British Baking Show.

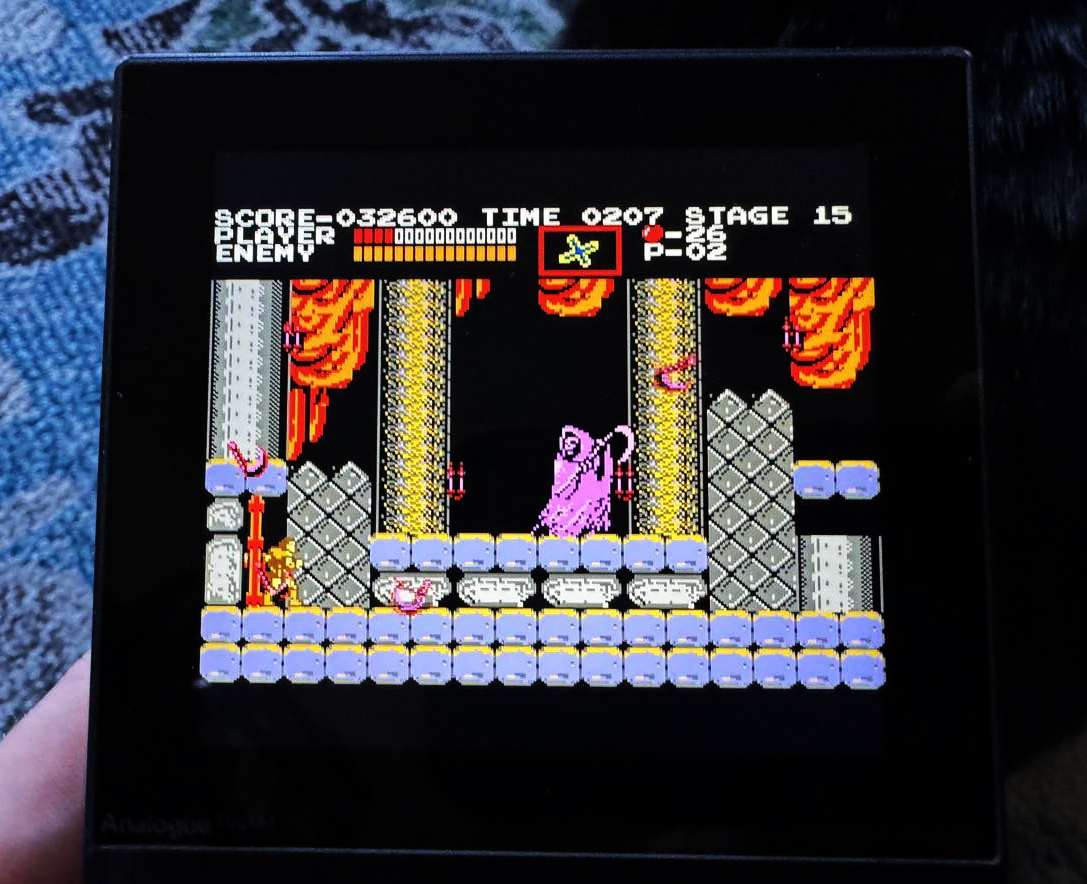

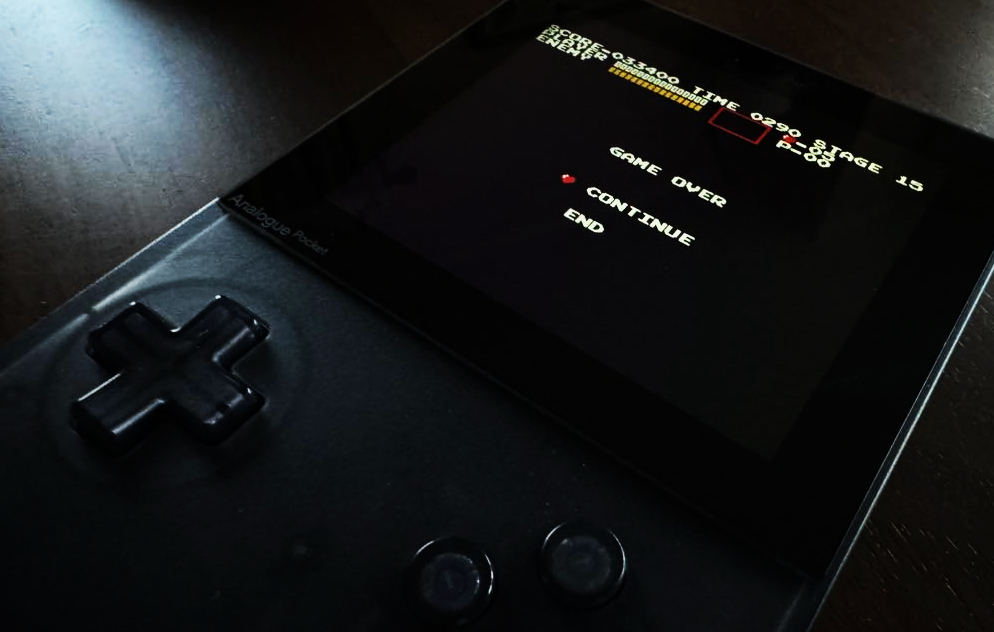

Sitting in the dark in front of the television with a belly full of soup, watching the marzipan-strewn cakes judged fresh from the oven, I decided to boot up my Analogue Pocket and try out Castlevania (1986). More recently, I’ve been working my way through the Castlevania series, jumping from game to game in no specific chronological order to see how the design evolved throughout the 1990’s and early 2000’s. I was aware of the first game’s difficulty going into it, but with save states active on my device, I figured, if anything, I might have some fun exploring what the game had to offer, antiquated gameplay aside.

To start, the movement is stiff. With the inability to move midjump, you find yourself committing yourself to a rigid leap that you realize immediately will have you colliding with a lethal projectile. Sometimes it’s something you should have seen coming, sometimes the enemy AI changes direction after you pressed your input. Either way, the deeper into the castle you go, the more punishments await.

I can see the developers wanting to create an experience catering to an older audience, with more realistic gameplay physics, darker thematic tones, and art direction that harkens back to early gothic horror films and Halloween decorations. When a lot of player avatars jumped and pivoted like children’s cartoon characters, Simon Belmont, the protagonist of the first Castlevania game, moved like a regular man and all the limits that come with that. In some ways we see echoes of this in Last of Us (2013), a game that sometimes feels clunky on purpose as we roleplay a man past his prime.

I am not going to critique this nearly 40-year-old game. All I’ll say is that it’s not to my taste but I appreciate the game for what it is. If you’re curious, I’m now in the middle of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997), and it is my personal favorite of the five or so I’ve dipped into. What I would like to discuss is the contrasting emotions I had experiencing the unforgiving gameplay of Castlevania (1986) with The Great British Baking Show cycling on in the background. Both the game and the show present extremely difficult challenges that test the skill of the participant. Where they differ, in my opinion, is one is delivered with kindness and generosity, while the other is not (I’ll give you a hint: It’s Castlevania).

I am not going to critique this nearly 40-year-old game. All I’ll say is that it’s not to my taste but I appreciate the game for what it is. If you’re curious, I’m now in the middle of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997), and it is my personal favorite of the five or so I’ve dipped into. What I would like to discuss is the contrasting emotions I had experiencing the unforgiving gameplay of Castlevania (1986) with The Great British Baking Show cycling on in the background. Both the game and the show present extremely difficult challenges that test the skill of the participant. Where they differ, in my opinion, is one is delivered with kindness and generosity, while the other is not (I’ll give you a hint: It’s Castlevania).

The Great British Baking Show is, in a sense, as seemingly competitive as any other reality show in its elimination. Every week the judges send someone home based on their performance. What makes the show special is that the only real pressure on the contestants is from the challenges themselves. The warm, inviting kitchen sets are always in a tent on the grounds of a beautiful manor house, stocked with everything the baker needs for the competition, a wonderful setting for a cozy watch.

The judges, encouraging and knowledgeable, work alongside the playful hosts who keep the mood light and the momentum of the show moving forward. I’ve seen some contestants offer advice or assistance to others when they’re struggling, bringing a real sense of comradery and community. In some ways it feels like everyone’s already won. Their dreams have already come true. They’re on The Great British Baking Show and they get to spend several weekends of their summer baking food in a wonderful tent with equally passionate artisans.

The judges, encouraging and knowledgeable, work alongside the playful hosts who keep the mood light and the momentum of the show moving forward. I’ve seen some contestants offer advice or assistance to others when they’re struggling, bringing a real sense of comradery and community. In some ways it feels like everyone’s already won. Their dreams have already come true. They’re on The Great British Baking Show and they get to spend several weekends of their summer baking food in a wonderful tent with equally passionate artisans.

In the user manual of Castlevania, at the end of the HOW TO PLAY section, it reads:

“To begin, hit the START button, and your nightmare begins.”

It is a game where you die a lot.

“To begin, hit the START button, and your nightmare begins.”

It is a game where you die a lot.

You might think you are getting the hang of it, hitting a stretch of the game where you stop dying so much, but before long the game will offer a new map and a new set of ways for you to die. You accidentally hit a gorgon head flying down a corridor, you die. A merman jumps out of a lagoon and clips the edge of your foot, you die. You miss a concise jump onto a narrow platform, you die. You replay the level up to that point and you miss again. You run out of lives and go all the way back to the beginning of the stage.

Death actually appears in Castlevania (1986), as a boss at the end of Stage 15, supplying an endless barrage of spinning scythes as he floats around the screen. Touch anything and you take damage. Die. Load state. Repeat. You saved state before the fight and still die 50 times before somehow defeating him with a sliver of life left. Your triumph is short lived as you realize that the game not only isn’t over but will just get more difficult. You’ve overcome death and still there’s no mercy. You look up, Paul Hollywood is shaking Liam’s hand for a job well done and you feel proud of him. His dessert looks amazing but you have Covid so your appetite is gone and food tastes weird anyway. You reset your Analogue Pocket and boot up Super Castlevania IV (1991) for the SNES to see if it’s a more forgiving experience. It is.

I played through more than half of Castlevania (1986) until I felt I’d played enough. I could have used save states more, but there’s a point where spamming save states makes you feel like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day going on date after date with his coworker. Sure, it’ll get you further, but the experience is off. At that point, I’ll just go to YouTube and watch a speedrun.

Some people reading this may be thinking “why would you play that? where’s is the fun in such a repetitive and unforgiving game?” while others may be thinking “why complain about a game that's supposed to be hard? If you don’t like that style of game, why keep playing? If you can’t get good, why not give up and play Kirby’s Adventure?” Both are valid takes.

Some people chase the difficulty and that satisfies them. I’ve been there. I beat Cup Head and Hollow Knight. Those games are hard, and you feel the tension thicken as you play. You study the moves you need to make and realize the mistakes that are getting you killed over and over again. Eventually, through patience, muscle memory, and study, you win. All that tension you experienced over the last fifteen minutes or thirty minutes or an hour (however long it takes) dissipates in an instant and you feel like every player of the Kansas City Chiefs the moment the ball makes it into the endzone with three seconds left on the clock. Confetti bursts through your brain. You keep playing because that feels good and the next time you reach a seemingly impossible stint of gameplay, you know that feeling will come but not exactly when it will come. Mastering a specific game isn’t too far off from the empowerment you feel learning a new instrument or mastering a difficult song. I don’t always chase this, but when I like the art and the game feels good to play, I’ll stick it out.

Some people reading this may be thinking “why would you play that? where’s is the fun in such a repetitive and unforgiving game?” while others may be thinking “why complain about a game that's supposed to be hard? If you don’t like that style of game, why keep playing? If you can’t get good, why not give up and play Kirby’s Adventure?” Both are valid takes.

Some people chase the difficulty and that satisfies them. I’ve been there. I beat Cup Head and Hollow Knight. Those games are hard, and you feel the tension thicken as you play. You study the moves you need to make and realize the mistakes that are getting you killed over and over again. Eventually, through patience, muscle memory, and study, you win. All that tension you experienced over the last fifteen minutes or thirty minutes or an hour (however long it takes) dissipates in an instant and you feel like every player of the Kansas City Chiefs the moment the ball makes it into the endzone with three seconds left on the clock. Confetti bursts through your brain. You keep playing because that feels good and the next time you reach a seemingly impossible stint of gameplay, you know that feeling will come but not exactly when it will come. Mastering a specific game isn’t too far off from the empowerment you feel learning a new instrument or mastering a difficult song. I don’t always chase this, but when I like the art and the game feels good to play, I’ll stick it out.

Generosity In Game Design

To compare the competition of The Great British Baking Show and the game design of Castlevania (1986), I would say that the former shows generosity, while the latter does not. I’ve been thinking about the concept of generosity in game design since writing about Celeste in last month’s newsletter. That is a game I steered clear of for a while as those who recommended it would first describe it as “incredible” followed by “but hard, very hard.” The game’s relatively low price point ($19.99) and it’s beautiful soundtrack (by composer Lena Raine) eventually brought me to purchase and play through the game despite its famed difficulty. I actually remember waiting for my drink order at Bourbon Coffee in Cambridge and hearing a song from Celeste’s soundtrack playing over the sound system and thinking to myself, “Alright, I’ve got to play this game.”

Footage of the original 2015 freeware version of Celeste produced in 4 days by Maddy Thorson and Noel Berry.

The challenges presented in Celeste are difficult [my death toll in Celeste was overall considerably higher than Castlevania (1986) even if you adjust for death per time played], but what makes the gameplay generous is everything you’re not fighting against. The controls are tight, so every input you make is predictably rendered onscreen. There is no added difficulty in trying to account for a character’s gravity or a delay in their movement. Once you’ve reached a flow state, your vision is fixed to the screen. Everything else falls away, and your thumbs’ movements are one with Madeline, the protagonist of Celeste. Not all challenges in Celeste are necessary to complete on your first run through a level, meaning that the added difficulty of collecting everything can be skipped early on and left as something you can revisit later if you’d like. When you do die, you don’t have to go back to the beginning or a much earlier checkpoint, just to replay the same difficult feats just to fail at a hard challenge at the end of the level only to die and play through that same 10-minute chunk of the game to get another chance to overcome that obstacle again. We don’t learn a song by playing through it from the beginning every time. Focus is on different sections, with focus on one section at a time before eventually mastering the totality of the piece to play it through from the beginning to the end.

One major theme in the game is overcoming obstacles, whether physical (climbing a mountain) or emotional (facing yourself). Just two minutes into the game, after Madeline survives a near-death experience, running fast across a collapsing bridge before performing a hail Mary jump to grab on to a cliff’s ledge, the music cuts out leaving just the sound of the wind on the mountain. White text appears across a dark blue background: “You can do this.” Celeste is difficult, and Celeste is about difficulty. Difficulty denotes failure, but when failure isn’t a finite state and you have the option to try again, you do.

Back in my January newsletter, I wrote about paring back unnecessary game mechanics, simplifying the gameplay to deliver a sharper experience to the player, and I think Celeste’s team of developers (a small team led by Maddy Thorson) did this masterfully. There are no crafting collectables, no skill trees, and no level buffs, just exactly what needs to be included for what the game is. Maddy Thorson has an article published on her website about different small ways the mechanics were crafted to deliver, as she puts it, “important parts of the moment-to-moment experience of Celeste.” The first example she gives is implementing “Coyote time,” the ability to jump for a moment in midair right after you have stepped off a ledge. Named after Wile E. Coyote’s cartoonish ability to slide off a ledge without immediately plummeting off a cliff, this subtle ability offers the player a little wiggle room when traversing platforms and cuts down on the amount of times you yell “but I was on the ledge!” whether you technically were or not. You can read that entire article HERE.

Nicolas Kraj, veteran game designer and former UX Director for Ubisoft, lists some other ways developers have programmed this type of generosity in his blog post Game Design Dirty Little Secrets on his site GD KEYS. To list a few: design smaller hitboxes to make projectiles easier to avoid (Enter the Gungeon), give the player a hidden bonus if they’ve failed too many times in a row (XCOM), or program the player’s last sliver of health to last longer than it should (System Shock). The best teachers, in my opinion, deliver challenges to students that push them to grow with generosity and kindness, empowering the student. Harshness can demotivate. Harshness can make you feel powerless in the face of failure. Not every game needs to be generous, but I appreciate it when I encounter it, especially in a hard-as-nails game.

Nicolas Kraj, veteran game designer and former UX Director for Ubisoft, lists some other ways developers have programmed this type of generosity in his blog post Game Design Dirty Little Secrets on his site GD KEYS. To list a few: design smaller hitboxes to make projectiles easier to avoid (Enter the Gungeon), give the player a hidden bonus if they’ve failed too many times in a row (XCOM), or program the player’s last sliver of health to last longer than it should (System Shock). The best teachers, in my opinion, deliver challenges to students that push them to grow with generosity and kindness, empowering the student. Harshness can demotivate. Harshness can make you feel powerless in the face of failure. Not every game needs to be generous, but I appreciate it when I encounter it, especially in a hard-as-nails game.

For Dungeons & Dragons, the dungeon master historically rolls their die behind a cardboard screen to keep their notes and rolls out of the eyes of the players. I’ve heard some will lie about certain rolls of the die every so often to go easier on the player in the name of fun. Instead of allowing a boss to kill a player’s character, why not let the character escape battle by the skin of their teeth? If the player has failed to succeed at lockpicking four times in a row, why not lower the difficulty on that fifth attempt? Coding these polished edges into a game can make for a better play experience, one that they won’t want to put down.

Sad Land Development Update

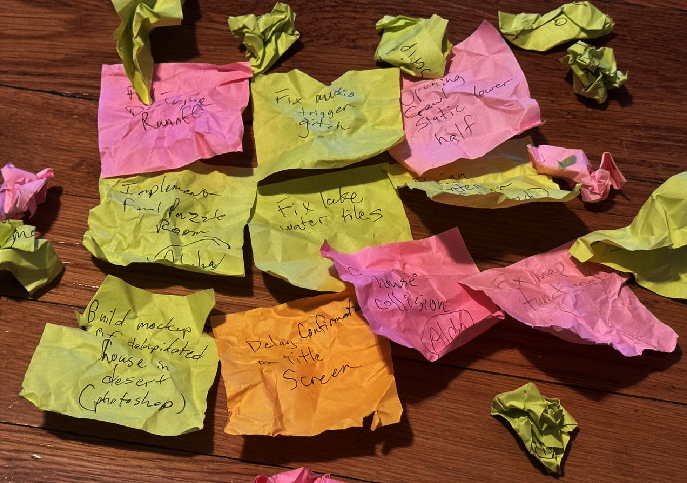

Sad Land development is moving along slowly but surely. With Good Friday off from work, I spent the morning at my local café, putting in a few hours of development time. This week I emptied a cup I’d been using as a receptacle for discarded post-its. Each note scrawled with some development task, plucked from my wall once completed and then discarded. It was nice to read some of these and mull over how many completed items I’ve surmounted to bring the project to where it is today.

Next month I’ll be sharing some of the reasons why NES games were so hard. I did a bunch of research that I ended up cutting out of this newsletter, but it’s too interesting not to share.

Sincerely,

Neil